持续性血流代谢耦合的证据

持续性血流代谢耦合的证据

# 持续性血流 - 代谢耦合的证据

缩略语

| ABB | fullText | 译文 |

|---|---|---|

| CMRglc | cerebral metabolic rate for glucose | 脑葡萄糖代谢率 |

| MAC | minimum alveolar concentration | 最低肺泡浓度 |

| 2-DG | 2-deoxyglucose | 2 - 脱氧葡萄糖 |

| [ 14C ] IAP | [ 14 C ] iodoantipyrine | [ 14 C ] 碘安替比林 |

| CBF | cerebral blood flow | 脑血流量 |

| CMR | cerebral metabolic rate | 脑代谢率 |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee | 动物关怀和利用委员会 |

# 摘要

The Role of Cerebral Metabolism in Determining the Local Cerebral Blood Flow Effects of Volatile Anesthetics: Evidence for Persistent Flow-Metabolism Coupling

Hansen TD, Warner DS, Todd MM, Vust LJ. The role of cerebral metabolism in determining the local cerebral blood flow effects of volatile anesthetics: evidence for persistent flow-metabolism coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9(3):323-328. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.1989.50

脑代谢在决定挥发性麻醉药局部脑血流效应中的作用:持续性血流 - 代谢耦合的证据

Hansen TD, Warner DS, Todd MM, Vust LJ. The role of cerebral metabolism in determining the local cerebral blood flow effects of volatile anesthetics: evidence for persistent flow-metabolism coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9(3):323-328. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.1989.50

Summary: The effects of equipotent doses of halothane (1.05%) versus isoflurane (1.38%) anesthesia on CMRglc were determined autoradiographically using the 2-[ 14C ]deoxyglucose technique in the rat. Eight anatomically standardized coronal sections were selected and digitized from the autoradiographs. Mean CMRglc was determined for hemispheric, neocortical, and subcortical regions at each anatomic level, and a neocortical / subcortical CMRglc ratio was calculated. In addition, the current CMRglc autoradiographs, as well as previous CBF autoradiographs obtained under identical experimental conditions were examined to characterize and compare flow/metabolism relationships for the two anesthetics. For this analysis, CBF was determined in 80 selected anatomic areas, and the values from each area were plotted against CMRglc values obtained from identical areas. In all major regions, mean CMRglc was greater with halothane than with isoflurane. The neocortical/subcortical ratio, reflecting the pattern of CMRglc distribution, was also greater during halothane anesthesia. This suggests that isoflurane has a disproportionate effect on neocortical metabolism resembling patterns previously seen for CBF. Analysis of CBF versus CMRglc plots for each anesthetic group showed two parallel lines with nearly identical slopes, but different Y intercepts. We conclude that the distribution of CMRglc observed during 1 MAC (minimum alveolar concentration) halothane and isoflurane anesthesia parallels the distribution of CBF. This finding supports the conclusion that flow-metabolism coupling is intact during halothane and isoflurane anesthesia, and that drug induced changes in cerebral metabolism may play an important role in determining the CBF response to that drug. Furthermore, there is evidence that, at a given level of CMRglc, isoflurane may have greater vasodilating capabilities than halothane.

Key Words: Anesthetics, volatile: halothane, isoflurane-Autoradiography-Brain blood flow-Cerebral metabolism.

摘要:用 2-[ 14C] 脱氧葡萄糖放射自显影技术测定了等剂量氟烷 (1.05%) 和异氟醚 (1.38%) 麻醉对大鼠 CMRglc 的影响。从放射自显影中选择 8 个解剖标准化的冠状切片并进行数字化处理。在每个解剖水平测定大脑半球、新皮质[1]和皮质下区域的平均 CMRglc,计算新皮质 / 皮质下的 CMRglc 比值。此外,检查了当前的 CMRglc 放射自显影,以及在相同的实验条件下获得的先前的脑血流自显影,以代表并比较两种麻醉剂的血流 / 代谢关系。在这项分析中,测定了 80 个选定解剖区域的 CBF,并将每个区域的值与从相同区域获得的 CMRglc 值绘制成图。所有主要区域,氟烷的平均 CMRglc 都大于异氟烷。在氟烷麻醉期间,反映 CMRglc 分布模式的新皮质 / 皮质下的比率也较大。这表明异氟醚对新皮质代谢有不成比例的影响,类似于以前看到的 CBF 模式。对每个麻醉组的 CBF 和 CMRglc 图的分析显示,两条平行线的斜率几乎相同,但 Y 截距不同。我们的结论是,在 1MAC (肺泡最低浓度) 氟烷和异氟醚麻醉时,CMRglc 的分布与 CBF 的分布是平行的。这一发现支持了在氟烷和异氟醚麻醉过程中血流 - 代谢偶联是完整的这一结论,药物引起的脑代谢变化可能在决定药物对脑血流的反应中发挥重要作用。此外,有证据表明,在给定的 CMRglc 水平上,异氟醚可能比氟烷具有更强的血管扩张能力。

关键词:麻醉剂,挥发性:氟烷,异氟烷 - 放射自显影 - 脑血流 - 脑代谢。

# 前言

Employing the [ 14 C ] iodoantipyrine ( [ 14C ] IAP ) autoradiographic method, we recently demonstrated that while 1.0 MAC (minimum alveolar concentration) halothane and isoflurane had similar effects on hemispheric (whole brain) CBF in the rat, markedly different flow distribution patterns within that hemisphere were produced by each agent (Hansen et aI., 1988). In particular, halothane produced a disproportionate increase in neocortical blood flow (relative to flow in subcortical structures), while flow distribution patterns seen with isoflurane were much more uniform. The reasons for these differing effects of volatile agents on regional flow distribution remain unknown-but it is almost certainly not a simple matter of the drugs having different intrinsic vasodilating potencies. If this were the case, it would be difficult to explain the unique flow distribution patterns seen for each agent.

A more likely explanation for the differences in regional CBF during halothane versus isoflurane anesthesia may be their differing effects on cerebral metabolism. Isoflurane is a more potent metabolic depressant than is halothane (perhaps in keeping with its more pronounced ability to reduce cerebral electrical activity) (Cucchiara et aI., 1974; Todd and Drummond, 1984; Maekawa et aI., 1986). In the conscious state, CBF and metabolism are interrelated ("coupled"), such that increases (decreases) in metabolism (CMR) are accompanied by increases (decreases) in CBF (Olesen, 1971; Sokoloff, 1981). However, the role of metabolic changes in controlling blood flow during anesthesia is unclear. It has long been believed that volatile agents "uncouple" flow and metabolism (i.e., increase CBF, decrease CMR) (Kuramoto et aI., 1979; Lassen and Shapiro, 1981). In spite of this belief, recent work suggests that this may not be true. Drummond et aI. (1986), working in rabbits, showed that when differences in the metabolic responses to halothane and isoflurane were removed (by barbiturate loading), both agents had identical effects on CBF. This would suggest that "coupling" may play an important role in defining the CBF response to these agents under normal circumstances. In other words, the lower metabolism associated with isoflurane may act, via a coupled vasoconstriction, to attenuate the independent vasodilating effect of the drug, with the result being only small changes in CBF. By contrast, since halothane has a smaller effect on CMR, less indirect, metabolically mediated vasoconstriction would be expected, direct vasodilation would be "unopposed," and the observed flows would be higher.

To further examine the possible role of metabolism in defining global and regional CBF responses to the volatile anesthetics, we performed a comparative examination of the effects of 1 MAC halothane versus isoflurane on local CMRglc using the 2-[ 14 C ] deoxyglucose autoradiographic method (Sokoloff et aI., 1977). Regional CMRglc values were then compared with regional [ 14 C ] IAP autoradiographic CBF data obtained under identical circumstances in an earlier experiment (Hansen et aI., 1988). To better provide evidence confirming the presence or absence of a coupled relationship between flow and metabolism, both current CMR data and our earlier CBF data were reexamined, and a structure by structure comparison of CBF and CMRglc was performed.

Based on these studies, we believe that a strong case can be made that coupling between flow and metabolism persists during 1 MAC concentrations of halothane and isoflurane, and that differences in the cerebral metabolic response to these drugs plays an important role in the flow patterns seen.

用 [ 14 C ] 碘安替比林 ([ 14 C ] IAP) 放射自显影方法,我们最近证明,虽然 1.0MAC (肺泡最低浓度) 氟烷和异氟烷对大鼠大脑半球 (全脑) CBF 有相似的影响,但每种药物在该半球内产生的血流分布模式明显不同 (Hansen et Ai.,1988)。特别是,氟烷导致新皮质血流不成比例地增加 (相对于皮质下结构中的血流),而异氟烷的血流分布模式更为均匀。挥发性药物对局部血流分布产生这些不同影响的原因尚不清楚,但几乎可以肯定的是,这不是药物具有不同的内在血管扩张效力的简单问题。如果是这样的话,就很难解释每个药剂所看到的独特的流动分布模式。

氟烷和异氟醚麻醉期间局部 CBF 差异的一个更可能的解释可能是它们对大脑新陈代谢的不同影响。异氟烷是一种比氟烷更有效的代谢抑制剂 (可能与其更显著的减少脑电活动的能力一致)(Cucchiara 等人,1974;Todd 和 Drummond,1984;Maekawa 等人,1986)。在有意识状态下,CBF 和代谢是相互关联的 (“耦合”),因此代谢 (CMR) 的增加 (减少) 伴随着 CBF 的增加 (减少)(Olesen,1971;Sokoloff,1981)。然而,在麻醉过程中代谢变化在控制血流方面的作用尚不清楚。长期以来,人们一直认为挥发性麻醉药使血流和新陈代谢 “分离”(即增加 CBF,降低 CMR)(Kuramoto et Ai.,1979;Lassen and Shapiro,1981)。尽管有这种认识,但最近的研究表明,这可能不是真的。Drummond et Ai.。(1986),在兔身上的研究表明,当消除对氟烷和异氟烷的代谢反应的差异时 (通过巴比妥酸盐负载),这两种药物对 CBF 具有相同的效果。这表明,在正常情况下,偶联可能在定义对这些药物的 CBF 反应中发挥重要作用。换句话说,与异氟醚相关的低代谢可能通过耦合的血管收缩作用来减弱药物的独立血管扩张作用,结果只是 CBF 的微小变化。相反,由于氟烷对 CMR 的影响较小,预计间接的、代谢介导的血管收缩作用较少,直接血管扩张将是 “非对立的”,观察到的流量将更高。

为了进一步研究代谢在确定对挥发性麻醉药的整体和局部 CBF 反应中的可能作用,我们使用 2-[ 14 C ] 脱氧葡萄糖放射自显影方法对 1MAC 氟烷和异氟烷对局部 CMRglc 的影响进行了比较研究 (Sokoloff 等人,1977)。然后将区域 CMRglc 值与早期实验 (Hansen et Ai.,1988) 中在相同情况下获得的区域 [ 14 C ] IAP 放射自显影 CBF 数据进行比较。为了更好地证实血流和代谢之间是否存在耦合关系,重新检查了当前的 CMR 数据和我们早期的 CBF 数据,并对 CBF 和 CMRglc 进行了逐个结构的比较。

基于这些研究,我们认为一个强有力的案例是,在氟烷和异氟烷的 1MAC 浓度范围内,血流和代谢之间的耦合持续存在,并且大脑对这些药物的代谢反应的差异在所看到的血流模式中起着重要作用。

# 方法

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 310 and 390 g (Biolabs; St. Paul, MN) were fasted for 6 h. Rats were randomly anesthetized with 1.5% halothane or 2.0% isoflurane in 33% O2 / balance N2. A tracheostomy was performed, and the animal connected to a small animal ventilator set to a tidal volume of 2.5 ml and a respiratory rate of 60/min. Femoral arterial and venous catheters were inserted via cutdown and all wound sites were infiltrated with 2.0% lidocaine. The arterial catheter was connected to a transducer for blood pressure monitoring, while the venous catheter was used for drug and fluid administration. Heparin (200 I.U.) and D-tubocurarine (2 mg) were administered intravenously to each rat.

Total surgical preparation time was 35 min (measured from the time of anesthesia induction). Immediately following completion of surgery, the inspired anesthetic agent concentration (measured with Puritan Bennetl Datex Model 222 Anesthetic Agent Analyzer) was reduced to either 1 MAC halothane (1.05%) or 1 MAC isoflurane (1.38%) in 33% O2 / balance N2 (White et aI., 1974). Rats remained anesthetized an additional 35 min prior to initiation of CMRglc determination. During this time, the ventilator was adjusted to maintain normoxia (PaO2 = 110 - 140 mm Hg) and normocarbia (PaCO2 = 38 - 42 mm Hg). Body temperature was monitored via a rectal probe and maintained within the range of 36.8°-37.2°C by surface heating or cooling. Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was continuously monitored and maintained within the range of 90 to 100 mm Hg by infusion of whole donor rat blood.

这项研究得到了机构动物关怀和利用委员会的批准。雄性 SD 大鼠 (Biolabs,St.Paul,MN) 体重在 310~390g 之间,禁食 6h,用 1.5% 氟烷或 2.0% 异氟烷在 33% O2 / 平衡 N2 中麻醉。进行气管切开术,将动物连接到小动物呼吸机上,潮气量为 2.5ml,呼吸频率为 60 次 / 分钟。切开置入股动、静脉导管,所有创面均注入 2.0% 利多卡因。动脉导管与传感器相连,用于血压监测,静脉导管用于药物和液体给药。肝素 (200I.U.)。右旋筒箭毒碱 (2 Mg) 静脉注射。

手术总准备时间为 35min (从麻醉诱导时间开始计算)。手术完成后,立即将吸入麻醉剂浓度 (用 Puritan Bennetl Datex 型 222 型麻醉剂分析仪测量) 在 33% O2 / 平衡 N2 中降至 1MAC 氟烷 (1.05%) 或 1MAC 异氟烷 (1.38%)(White et Ai.,1974)。大鼠在开始 CMRglc 测定前另外 35 分钟保持麻醉状态。在此期间,呼吸机被调整为保持常压 (PaO2 =110-140 mm Hg) 和常压 (PaCO2 =38-42 mm Hg)。通过直肠探头监测体温,并通过表面加热或降温将体温维持在 36.8°-37.2°C 范围内。通过输注供体大鼠全血,持续监测平均动脉压 (MABP),并维持在 90~100 mm Hg 范围内。

Thirty-five minutes after the end of surgery, animals were given 2 ml whole blood. Final MABP and arterial blood gas values were recorded and 100 μCi/kg of 2-[ 14 C ] deoxyglucose (2-[ 14 C ] DG, specific activity 50-56 mCi/mmol, New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) was infused intravenously at a constant rate over 30 s via an infusion pump. At defined time intervals over the next 45 min, fourteen 100-μl arterial blood samples were collected. Samples were immediately centrifuged and the plasma saved for later determination of 14C activity and glucose concentration. The animals were then decapitated, the brains rapidly removed and frozen immediately in 2-methylbutane (- 40°C). Twenty microliters of each timed arterial plasma sample was placed on chromatography paper and dried for 24 h, then eluted 24 h in 1 ml water and 9 ml liquid scintillation cocktail (Ready-Solv HP/b, Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting (Searle, Model 6880, Des Plaines, IL) using an external quench correction. Plasma glucose values were determined by the glucose oxidase method (Beckman Glucose Analyzer-2, Fullerton, CA). Animals in which subsequent plasma glucose values deviated more than 10% from baseline levels were excluded from the study.

手术结束 35 分钟后,给予动物 2 毫升全血。记录末次平均动脉压和动脉血气值,并通过输液泵以恒定速率静脉输注 100 μCi/kg 的 2-[ 14 C ] 脱氧葡萄糖 (2-[ 14 C ] DG,比活度 50-56 mCi/mmol,新英格兰核,波士顿,马萨诸塞州)。在接下来的 45 分钟内,在规定的时间间隔内,采集 14 个 100-μl 动脉血样。样品立即离心,血浆保存以备以后测定 14C 活性和葡萄糖浓度。然后将动物处死,迅速取出大脑,立即用 2 - 甲基丁烷 (-40°C) 冷冻。每个定时的动脉血浆样品 20 微升放在层析纸上干燥 24 h,然后在 1ml 水和 9ml 液体闪烁鸡尾酒 (Ready-Solv HPIb,Beckman,Fullerton,CA) 中洗脱 24 h。放射性通过液体闪烁计数 (Searle,Model 6880,Des Plaines,IL) 使用外部猝灭校正来测定。用葡萄糖氧化酶法 (Beckman 葡萄糖分析仪 - 2,加利福尼亚州富勒顿) 测定血糖值。随后血糖值偏离基线水平超过 10% 的动物被排除在研究之外。

Brains from eight halothane and eight isofluraneanesthetized animals were analyzed. Frozen brains were cut in 20 fLm thick serial coronal sections on a cryostat ( - 20°C). Quadruplicate sections taken at 240 μm intervals were mounted on glass slides, dried for 5 min on a hot plate (50°C), and exposed to Kodak SB-5 autoradiographic film for 10 days in an X-ray cassette along with seven [ 14 C ] methylmethacrylate standards (Amersham, Arlington Hts, IL). Autoradiographic images of eight standardized brain sections were chosen from each animal for further analysis, based upon anatomical land- marks (see Hansen et aI., 1988). These images were converted to digitized optical density images on a scanning microdensitometer system (Eikonix-Kodak, Bedford, MA.) with a camera aperture of 100 μm. Optical densities from these autoradiographic images, standard radioactivity values derived from 14C standards, and timed arterial blood radioactivity values were entered into a Digital Micro-Vax computer system. Recalculation of CMRglc values from brain images employed the equations developed by Sokoloff et ai. (1977) (lumped constant = 0.483), with mathematical operations performed using a quantitative glucose utilization program (A Toga, Washington Univ., St. Louis, MO).

对 8 只氟烷和 8 只异氟醚麻醉动物的脑进行了分析。冰冻脑在冰冻恒温器 (-20°C) 上连续切成 20 层厚的冠状切片。将以 240 μm 间隔拍摄的四份切片安装在玻璃片上,在加热板 (50°C) 上烘干 5 分钟,并在 X 射线盒式磁带中与 7 个 [ 14 C ] 甲基丙烯酸甲酯标准 (amersham,Arlington HTS,IL) 一起暴露在柯达 SB-5 放射自显影胶片中 10 天。根据解剖标记,从每只动物身上选择了 8 个标准化脑切片的放射自显影图像进行进一步分析 (参见 Hansen 等人,1988)。这些图像在扫描显微密度计系统 (Eikonix-Kodak,Bedford,MA) 上被转换为数字化的光密度图像。相机光圈为 100 μm。这些放射自显影图像的光密度、根据 14 C 标准得出的标准放射性活度值和定时的动脉血放射性活度值被输入到 Digital Micro-Vax 计算机系统。从脑图像中重新计算 CMRglc 值使用了 Sokoloff 等人开发的方程。(集总常数 = 0.483),使用定量葡萄糖利用程序 (A Toga,华盛顿大学,圣路易斯,密苏里州) 进行数学运算。

Two different analytical approaches were used. The first was very similar to that used for examination of regional CBF in our earlier experiment (Hansen et aI., 1988). Individual digitized CMRglc images were pseudocolor enhanced and displayed on a cathode ray screen. Using an operator-controlled cursor, regions of interest were circumscribed and mean CMRglc for each region recorded, along with the area of each region (in pixel units). The three primary regions of interest in each section were hemisphere, neocortex, and subcortex, where subcortex was defined as the total hemispheric area minus the area of the neocortical mantle (see Hansen et aI., 1988). Ventricular spaces were subtracted prior to calculations. Olfactory cortex is a limbic structure and was therefore included in subcortex (Hornykiewcz and Livingston, 1978). The neocortical and subcortical CMRglc values from each section were then used to calculate a neocorticaVsubcortical CMRillc ratio. "Whole brain" values for hemispheric, neocortical, and subcortical CMRglc as well as the neocortica/subcortical ratio were determined as area weighted averages of values from each of the eight sections in each rat. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOV A) (section level versus anesthetic with section level as a repeated variable) was then used to independently compare values for each region at each anatomic level as well as for the brain as a whole.

In addition to these large areas, ten anatomical structures were outlined and CMRglc for each determined (these structures are listed in Table 2). These CMRglc values were compared between anesthetic groups by an unpaired Student's t test.

The second analysis compared CMRglc values measured within 80 anatomically defined areas (representing 49 anatomic structures) to CBF values in corresponding areas, which were measured by reexamining digitized [ 14C] IAP autoradiographs obtained in our previous CBF study (Hansen et aI., 1988). Specifically, CBF and CMRglc images were pseudo-color enhanced and displayed on a cathode ray screen. Using an operatorcontrolled cursor, ten 500 square pixel unit areas were consistently identified on each of the same eight anatomically standardized brain sections from each animal and CBF and CMRglc values were determined from each area. These areas were selected to sample as many anatomically diverse areas as possible. Individual CBF and CMRglc values for each area were then averaged over all animals within an anesthetic group. Mean CMRglc values for each of 80 areas within an anesthetic group were then plotted versus corresponding mean CBF values from the identical regions. Best fit lines were determined for both groups from these CBF and CMRglc data points using a linear, least squares fit. Slopes and Y intercepts for each anesthetic group were compared using a regression analysis with indicator variables (Neter et aI., 1983). All CBF and CMRglc values are reported as mean ± standard deviation with significance assumed when p < 0.05.

使用了两种不同的分析方法。第一种方法与我们早期实验 (Hansen et Ai.,1988) 中用于检测局部脑血流量的方法非常相似。个别数字化的 CMRglc 图像被假彩色增强并显示在阴极射线屏幕上。使用操作员控制的光标,限定感兴趣的区域,并记录每个区域的平均 CMRglc,以及每个区域的面积 (以像素为单位)。每个部分的三个主要感兴趣区域是半球、新皮质和皮质下,其中皮质下的定义是半球总面积减去新皮质地幔的面积 (见 Hansen 等人,1988)。在计算前减去脑室空间。嗅皮层是一种边缘结构,因此被归入皮质下 (Hornykiewcz 和 Livingston,1978)。然后使用每个切面的新皮质和皮质下的 CMRglc 值来计算新皮质与皮质下的 CMRillc 比率。每只大鼠大脑半球、新皮质和皮质下的 CMRglc 以及新皮质 / 皮下比率的 “全脑” 值被确定为每只大鼠 8 个部分的面积加权平均值。然后使用双因素方差分析 (ANOVA)(节段水平与麻醉剂,节段水平为重复变量) 来独立比较每个解剖水平上的每个区域以及整个大脑的值。

除了这些大区域外,还概述了 10 个解剖结构,并确定了每个结构的 CMRglc (表 2 列出了这些结构)。麻醉组之间的 CMRglc 值通过非配对 Student's t 检验进行比较。

第二个分析比较了在 80 个解剖定义的区域 (代表 49 个解剖结构) 内测量的 CMRglc 值与相应区域的 CBF 值,这些值是通过重新检查在我们之前的 CBF 研究中获得的数字化 [ 14C] IAP 放射自显影 (Hansen 等人,1988) 来测量的。具体地说,CBF 和 CMRglc 图像被假彩色增强并显示在阴极射线屏幕上。使用操作者控制的光标,在来自每只动物的相同的 8 个解剖标准化脑切片的每一个上一致地识别出 10 个 500 平方像素的单位区域,并从每个区域确定 CBF 和 CMRglc 值。这些区域被选为尽可能多的解剖不同区域的样本。然后对麻醉组内所有动物的每个区域的单个 CBF 和 CMRglc 值进行平均。然后绘制麻醉组内 80 个区域的平均 CMRglc 值与相同区域的相应平均 CBF 值。使用线性最小二乘拟合从这些 CBF 和 CMRglc 数据点确定两组的最佳拟合线。使用带有指示变量的回归分析 (Neter et Ai.,1983) 对每个麻醉组的斜率和 Y 截距进行比较。所有 CBF 和 CMRglc 值均报告为平均值 ± 标准差,当 p<0.05 时假设显著。

# 结果

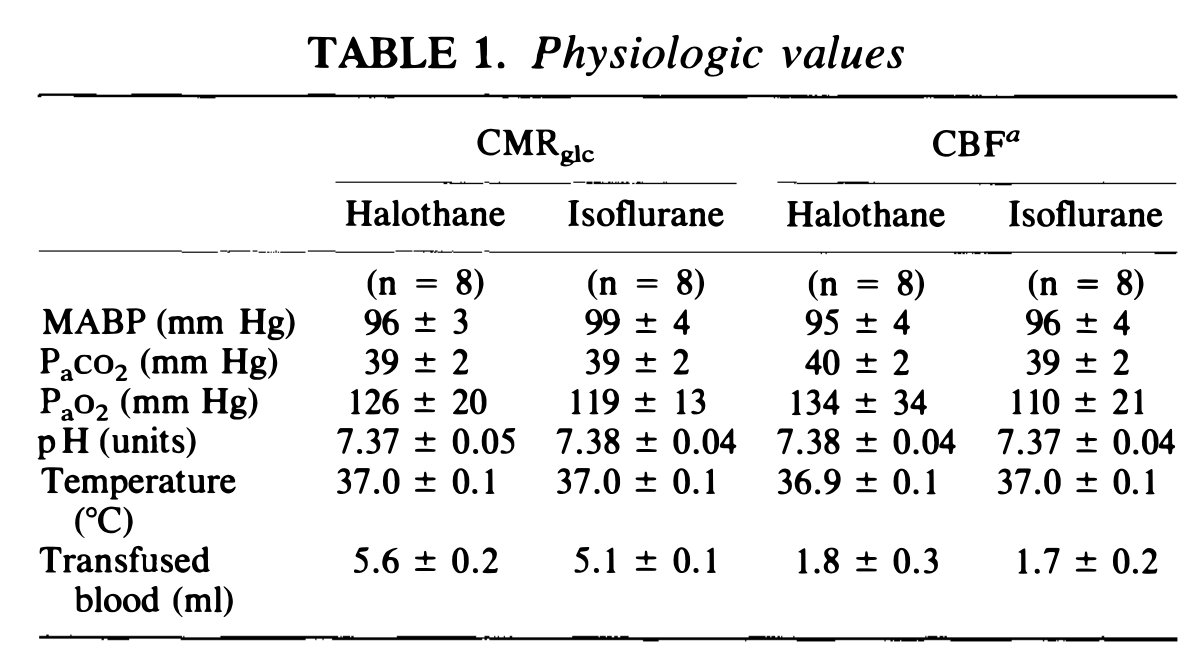

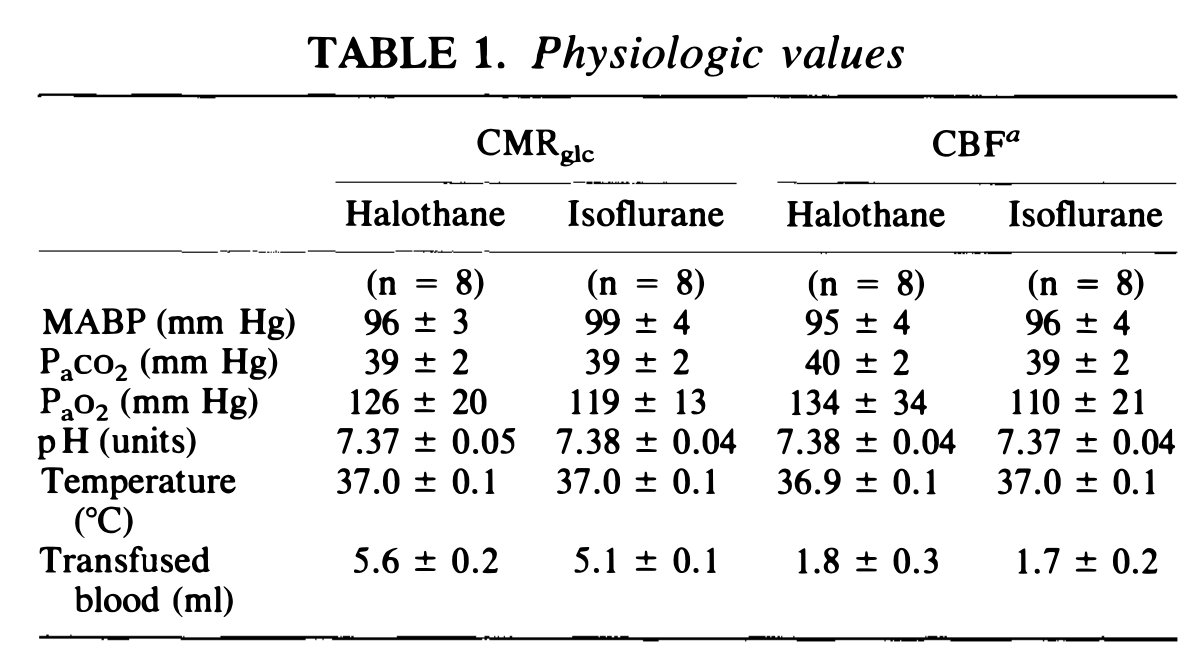

Physiologic values determined immediately prior to CMRglc determination are reported in Table 1, along with similar data from CBF animals. No significant intergroup differences were noted with respect to Pao2, Paco2, pH, MABP, or temperature. Larger amounts of infused blood were required to maintain MABP in the CMRglc groups because of larger volumes of blood samples drawn.

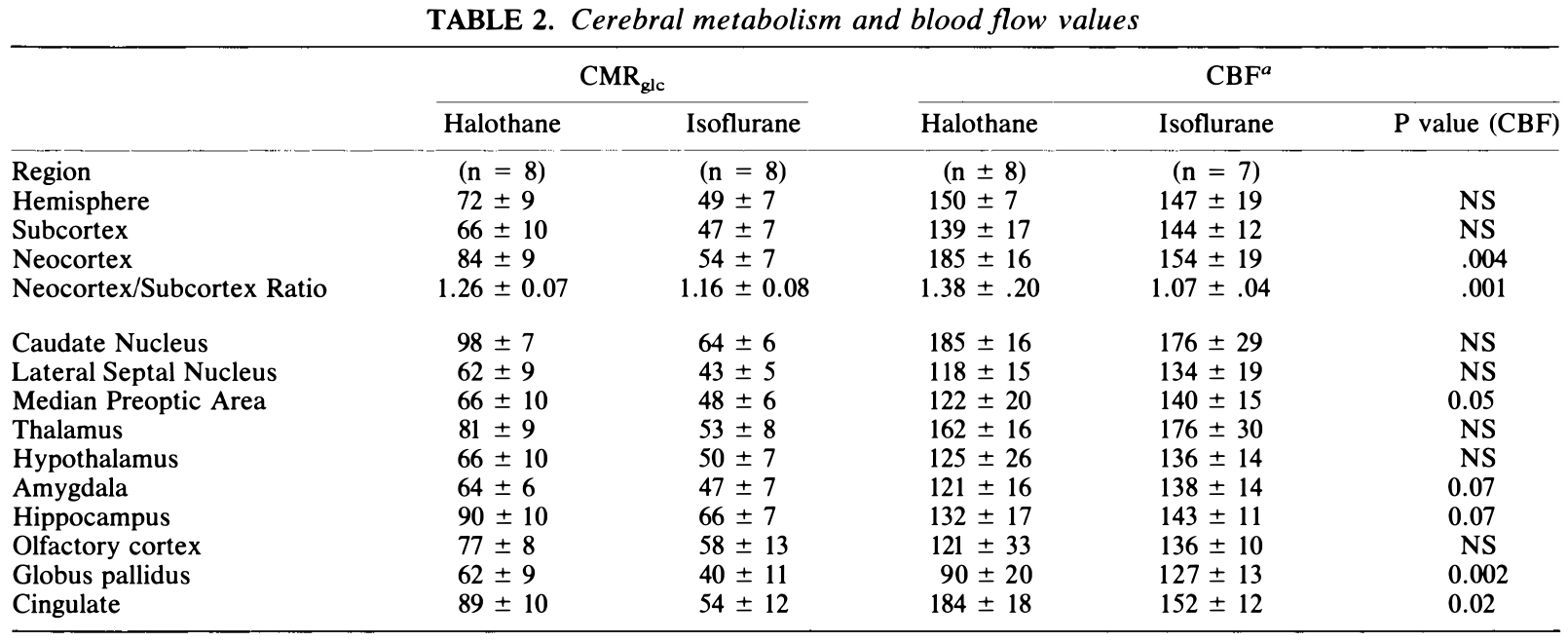

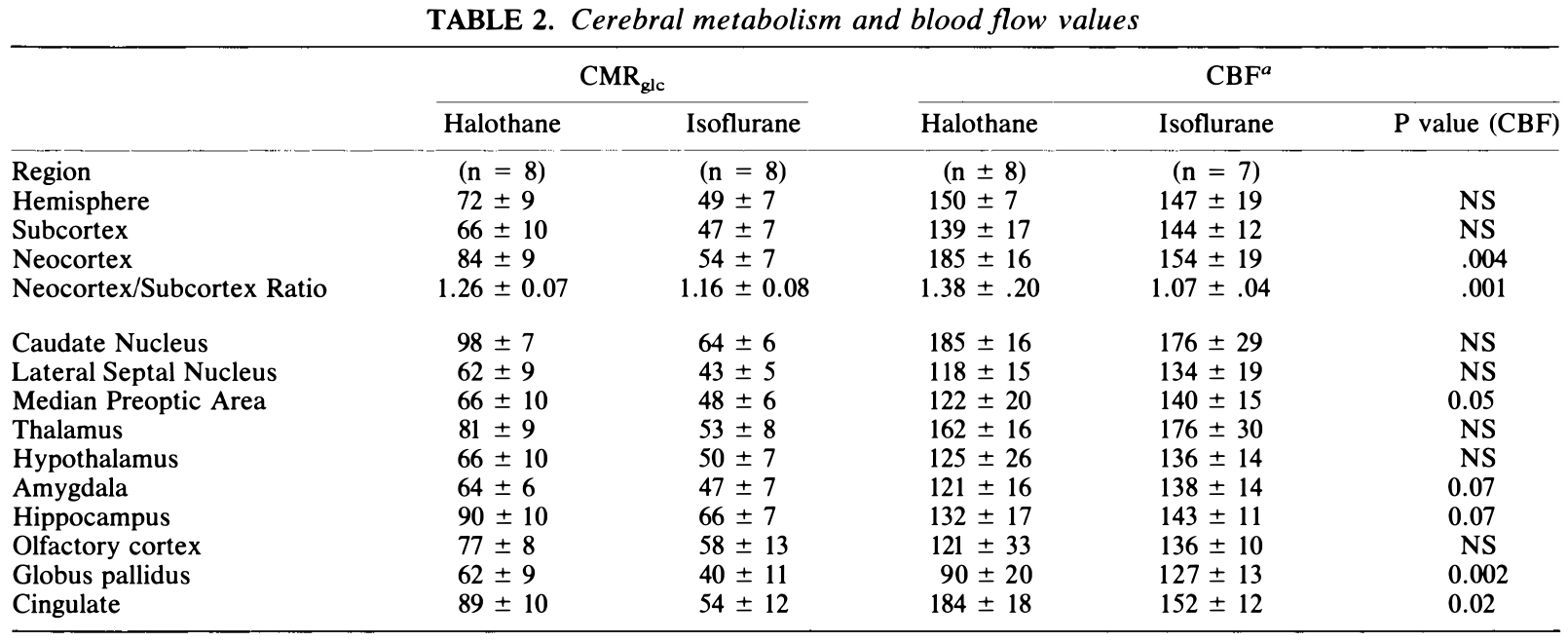

Table 2 summarizes our "whole brain" CMRglc results for the three major tissue regions, as well as values from ten anatomical regions. Average hemispheric, neocortical, and subcortical CMRglc values were lower in the isoflurane group (p < .001 for each region), as was the neocortica/subcortical ratio (p < .001). Local CMRglc was also lower in the isoflurane group for all local anatomical structures. Anatomically comparable data for CBF is also listed in Table 2.

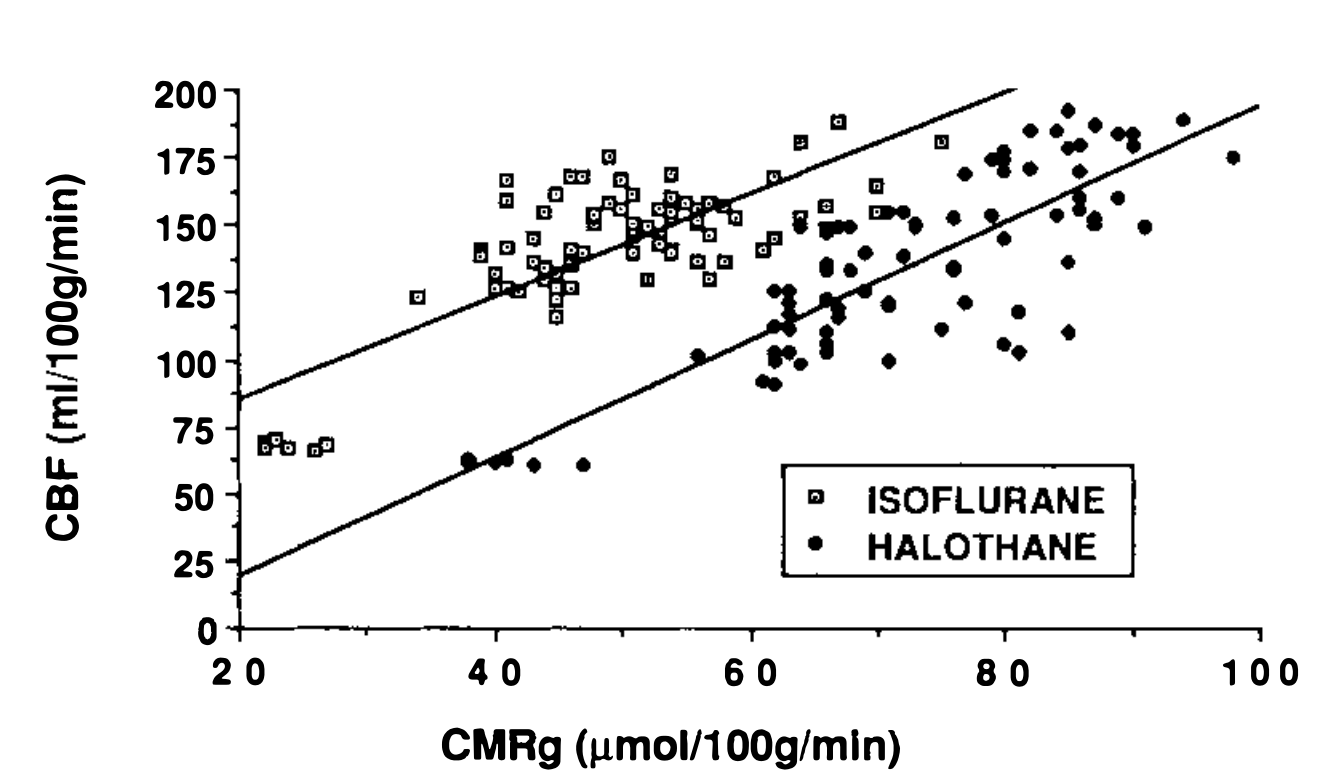

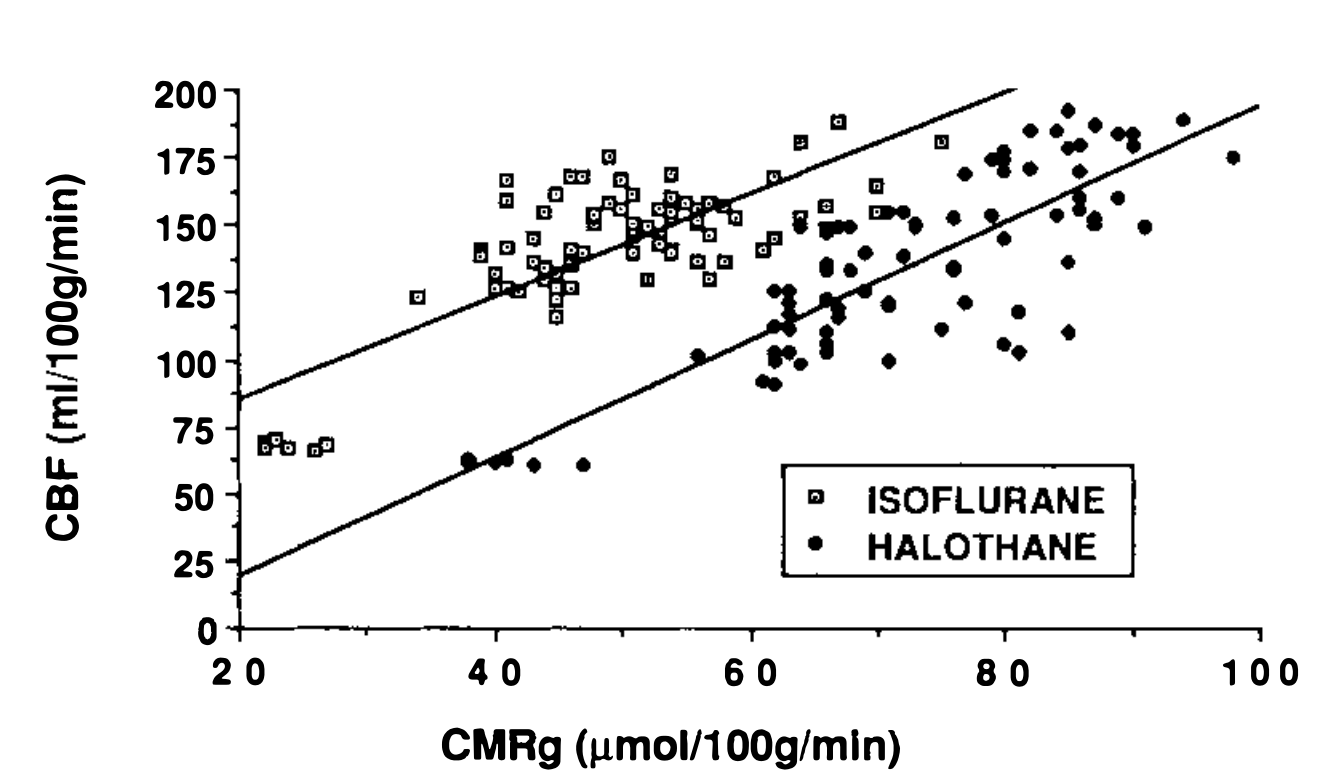

Mean CBF values from the 80 selected white and gray matter structures ranged from 59 to 195 ml 100g-1min-1 during halothane and isoflurane anesthesia; corresponding mean CMRglc values from the same structures ranged from 24 to 98 μmol 100g-1min-1. Regression analysis of CBF versus CMRglc values plotted on a structure by structure basis for each anesthetic group is shown in Fig. 1, and is represented by two distinct lines[

表 1 中报告了在 CMRglc 测定之前立即测定的生理值,以及来自 CBF 动物的类似数据。在 PaO2、PaCO2、pH、MABP 或温度方面没有明显的组间差异。在 CMRglc 组中,由于抽取了更多的血液样本,需要输入更多的血液来维持 MABP。

表 2 总结了我们的 “全脑” 三个主要组织区域的 CMRglc 结果,以及来自十个解剖区域的值。异氟醚组大脑半球、新皮质和皮质下的平均 CMRglc 值较低 (每个区域 P<.001),新皮质 / 皮质下比率也较低 (P<.001)。异氟醚组所有局部解剖结构的局部 CMRglc 也较低。表 2 还列出了 CBF 的解剖学可比数据。

在氟烷和异氟醚麻醉期间,80 个选定的白质和灰质结构的平均 CBF 值在 59 到 195ml 100g-1min-1 之间;相同结构的相应 CMRglc 平均值在 24 到 98 μmol 100g-1min-1 之间。图 1 所示为每组麻醉药按结构绘制的 CBF 与 CMRglc 值的回归分析,由两条不同的直线表示 [

Physiologic values (mean ± S.D.) controlled during the administration of 1 MAC halothane and 1 MAC isoflurane anesthesia. Values were recorded immediately before CMRglc or CBP determination. Body temperature and MABP were maintained between 36.8°-37.2°C and 90-100 mm Hg, respectively, throughout CMRglc and CBP determinations.

a Values for CBP groups as previously reported in Hansen et al. (1988).

在 1 个 MAC 氟烷和 1 个 MAC 异氟醚麻醉期间控制的生理值 (Mean±S.D.)。在 CMRglc 或 CBP 测定前立即记录数值。在 CMRglc 和 CBP 测量过程中,体温和 MABP 分别保持在 36.8°-37.2°C 和 90-100 mm Hg 之间。

a 代表 Hansen 等人之前报告的 CBF 组的数值。(1988)

CMRglc (μmol 100g-1min-1) and CBF (ml 100g-1min-1) values (mean ± S.D.) of selected regions during 1 MAC halothane versus 1 MAC isoflurane anesthesia (values above the line were area-weighted over eight brain sections). Statistical comparison indicated significance (p < .001) for all halothane vs isoflurane CMRglc values as well as the neocortex to subcortex ratio. P values for CBF comparisons listed at right. NS = not significant.

a Values for CBP groups as previously reported in Hansen et al. (1988).

CMRglc(μmol 100g-1min-1) 和 CBF (ml 100g-1min-1) 值 (Mean±S.D.)。在 1 个 MAC 氟烷麻醉和 1 个 MAC 异氟醚麻醉期间选择的区域 (线上的值是在八个脑切片上按面积加权的)。统计学比较显示,所有氟烷与异氟烷的 CMRglc 值以及新皮质与皮质下的比率均有统计学意义 (P<.001)。右侧列出了 CBF 比较的 P 值。NS = 不显著。

a 代表 Hansen 等人之前报告的 CBF 组的数值。

Cerebral blood flow (ml 100g-1min-1) vs CMRglc (μmol 100g-1min-1) for 80 selected regions calculated from brain auto radiographic images during 1 MAC halothane vs isoflurane anesthesia. For halothane, the regression line is described by: CBF = (2.19) CMRglc - 24, r = 0.84, while for isoflurane the line is: CBF = (1.90) CMRglc + 47, r = 0.78.

在 1MAC 氟烷与异氟醚麻醉过程中,根据脑自显影图像计算 80 个选定区域的脑血流量 (ml 100g-1min-1) 与 CMRglc(μmol 100g-1min-1)。对于氟烷,回归直线为:

# 讨论

In the nonanesthetized state, cerebral blood flow and metabolism are tightly coupled, such that increases or decreases in metabolism are accompanied by corresponding changes in blood flow (Olesen, 1971; Sokoloff, 1981; Kuschinsky et aI., 1981). Using the [ 14C] IAP and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) techniques to measure CBF and CMRglc' respectively, Greenberg et al. (1979) have demonstrated identical spatial distribution of flow and metabolism following vibrissal stimulation in the rat. Similarly, Silver (1978) has demonstrated rapid increases in microvascular flow following neuronal stimulation. These and many other studies indicate that normal flow is indeed regulated (in part) by changes in functional and metabolic activity.

Previous studies have examined CBF and CMRglc at various minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) levels of halothane and isoflurane anesthesia (Kuramoto et aI., 1979; Todd and Drummond, 1984; Maekawa et aI., 1986). These studies have shown that at increasing MAC levels, CBF increases while CMRglc is either unchanged or (more commonly) decreased. Based on these observations, some authors have concluded that the anesthetic agents studied caused an "uncoupling" of flow and metabolism.

In our current study, we have noted differences in the CMRglc effects of halothane and isoflurane, not just in terms of their absolute values, but also in terms of the spatial distribution patterns. Specifically we observed that not only was regional CMRglc lower with 1 MAC isoflurane than with 1 MAC halothane, but also that the ratio of neocortical to subcortical CMRglc was lower with isoflurane (Table 2). This observation suggests that isoflurane has a proportionately greater effect on neocortical CMRglc (relative to its overall CMRglc impact) than does halothane. Of greater importance, however, is that this CMRglc distribution reflects a pattern also seen for CBF under similar anesthetic conditions (Hansen et aI., 1988), with isoflurane-anesthetized rats having lower neocortical flows and lower neocortical/subcortical ratios than animals given halothane. In other words, anesthetic-related flow patterns are paralleled by patterns in metabolism. While this alone is evidence suggesting a relationship between these two variables, we have also demonstrated a linear relationship between CBF and CMRglc over a wide range of flow and CMRglc values during 1 MAC anesthesia with both agents; brain areas with high CMRglc values had higher measured flows, while areas with low CMRglc values had low CBF. This is identical to the linear relationship observed in awake animals-a relationship that is considered strong evidence for the existence of a coupled relationship between these two parameters. In short, these two findings suggest that flow and metabolism are, in fact, "coupled" during 1 MAC doses of both of these anesthetics. They also indirectly suggest that differences in metabolism produced by these agents may influence the changes in CBF produced by these drugs. This postulate could be better examined by recording both flow and metabolism in the same animal, before and after some intervention that is known to increase CMRglc, e.g., a seizure. If CBF and CMRglc are indeed "coupled," one would expect to see parallel increases in both values. Unfortunately, this demonstration is more difficult to carry out. The auto radiographic methods used in the current study are not compatible with such repeated measures, and the usual methods for recording "whole brain" CBF and CMR [e.g., 133Xe washout combined with arteriovenous (A-V) O2/glucose differences] are confounded by the fact that the calculation of CMR is dependent on the measurement of CBF (which makes a linear regression comparison of CBF versus CMR suspect). However, the work of Kuramoto et aI., ( 1979) using volumetrically determined CBF, identified parallel increases in CBF and CMR02 during peripheral stimulation in dogs breathing I MAC halothane-again evidence supporting our contention that flow and metabolism remain tightly coupled during the administration of clinically relevant concentrations of volatile anesthetics.

This conclusion has a number of important implications. Studies which have examined neocortical CBF have shown halothane to have greater effects than isoflurane (Todd and Drummond, 1984; Eintrei et aI., 1985; Scheller et aI., 1986). Based on these observations, it has been suggested that halothane has greater direct vasodilating capabilities than isoflurane (Shapiro, 1986). However, comparison of CBF during halothane versus isoflurane anesthesia when metabolic differences are minimized (barbiturate loading) indicates that this may not be true (Drummond et aI., 1986). This question can also be examined in our current study. As can be seen from the plots of CBF versus CMRglc in Fig. 1, the line for isoflurane is above that for halothane. This suggests that, at a given value of CMRglc, isoflurane anesthetized animals may have greater flows than animals given halothane. These observations suggest that despite a greater overall depression of CMRglc during isoflurane compared to halothane anesthesia, the potentially greater vasodilating capabilities of isoflurane may account for equal hemispheric flow values previously reported for the two agents (Theye and Michenfelder, 1968; Cucchiara et aI., 1974; Stullken et aI., 1977).

In the interpretation of our results, methodological considerations must be evaluated. First, the selection of large brain areas for our initial determination of CBF and CMRglc was somewhat different from the approach used by others (which is more similar to the multiple spot samples used in our second analysis). Furthermore, area weighted CMRglc values from eight standardized brain sections were taken to reflect whole brain values. However the brain sections chosen for analysis were based on subcortical anatomical structures within these sections, not the uniformity of anteroposterior distance between sections. Examination of the anatomical location of our selected sections shows a relative bias toward centrally located sections at the expense of more rostral and caudal sections. In the second analysis, eighty 500 square pixel unit areas, representing 49 independent anatomical brain structures, were consistently selected for CBF and CMRglc determination from identical anatomical sites over eight autoradiographic brain sections. These areas were selected to represent a wide range of CMRglc values, yet a sampling bias with relative exclusion of very low CMRglc values (white matter) is apparent. It is possible, although unlikely, that the inclusion of a greater number of these areas would alter our results.

Second, animals in the flow and metabolism studies were anesthetized for somewhat different periods of time prior to the initiation of CBF or CMRglc determinations ( 1 h 30 min versus 1 h 10 min respectively, measured from the time of induction). Due to the differences in time required to measure CBF versus CMRglc (45 s vs 45 min, respectively), an identical anesthetic exposure period for the two studies was difficult to establish. However, the majority of 2-DG utilization occurs early in the 45 min measurement period (Sokoloff et aI., 1977). Therefore, the anesthetic equilibration period in the metabolism study was chosen such that the midpoint of the CMRglc determination would closely approximate the 1 h 30 min total anesthetic exposure time allowed in the previous CBF study. As a result, animals in the CBF study groups versus those in the CMRglc study were exposed to the anesthetics studied for slightly different time periods. Since adaptation to anesthetic-produced changes in flow and metabolism occurs over several hours, the errors related to these small time differences would be expected to be minimal (Warner et al., 1985).

In summary, the relationship between CBF and CMRglc in a variety of anatomic brain structures during 1 MAC halothane and isoflurane anesthesia was best represented by two parallel lines with equal slopes, but different Y intercepts. This, combined with the similar CBF and CMRglc distribution patterns seen with a given agent, is strong evidence in support of the persistence of intact flowmetabolism coupling during 1 MAC anesthesia. In addition, at any given level of CMRglc, isofluraneanesthetized rats had greater CBF values. Whether this indicates that isoflurane is a more potent direct vasodilator, or whether other factors that influence CBF are being differentially altered by these drugs (e.g., neuronal input) remains to be determined. These observations may have further applications in experiments in which the effects of inhalational anesthetics are studied in the presence of an equally established level of CMR, such as barbiturate pretreatment. These findings also suggest, as was previously noted by Scheller et al. (1987) and Drummond et al. ( 1986), that the effects of an anesthetic agent on CBF may depend upon the preexisting metabolic state of the brain and that metabolic activity must be taken into consideration when drawing any conclusions about the mechanisms by which volatile agents alter flow.

在非麻醉状态下,脑血流和代谢是紧密耦合的,代谢的增加或减少伴随着相应的血流变化 (Olesen,1971;Sokoloff,1981;Kuschinsky et al.,1981)。Greenberg (1979) 使用 [ 14C] IAP 和 2 - 脱氧葡萄糖 (2-DG) 技术分别测量 CBF 和 CMRglc,证明刺激大鼠的 vibrissal 神经后,显示了相同的血流和代谢的空间分布。同样,Silver (1978) 也证明了神经元刺激后微血管流量的快速增加。这些和许多其他研究表明,正常的血流确实 (部分) 受到功能和代谢活动变化的调节。

以前的研究已经检测了不同最低肺泡浓度 (MAC) 水平的氟烷和异氟烷麻醉下的 CBF 和 CMRglc (Kuramoto et Ai.,1979;Todd and Drummond,1984;Maekawa et Ai.,1986)。这些研究表明,随着 MAC 水平的增加,CBF 增加,而 CMRglc 要么保持不变,要么 (更常见的) 减少。基于这些观察,一些作者得出结论,所研究的麻醉剂导致了血流和新陈代谢的解偶联。

在我们目前的研究中,我们注意到氟烷和异氟烷的 CMRglc 效应的不同,不仅在它们的绝对值方面,而且在空间分布模式方面。具体地说,我们观察到,使用 1MAC 异氟醚的局部 CMRglc 不仅低于使用 1MAC 氟烷的局部 CMRglc,而且使用异氟烷的新皮质和皮质下 CMRglc 的比率也更低 (表 2)。这一观察结果表明,异氟烷对新皮质 CMRglc 的影响 (相对于其总体 CMRglc 影响) 比氟烷大。然而,更重要的是,这种 CMRglc 分布反映了类似麻醉条件下 CBF 的模式 (Hansen et Ai,1988),与给予氟烷的大鼠相比,异氟醚麻醉的大鼠具有较低的新皮质血流量和新皮质 / 皮质下比率。换句话说,麻醉相关的血流模式与新陈代谢的模式是平行的。虽然这本身就是表明这两个变量之间存在关系的证据,但我们也证明了 CBF 和 CMRglc 在两种药物的 1 MAC 麻醉期间的大范围血流和 CMRglc 值之间存在线性关系;CMRglc 值高的脑区测量到的血流量较高,而 CMRglc 值低的区域 CBF 较低。这与在清醒动物身上观察到的线性关系是相同的 -- 这种关系被认为是这两个参数之间存在耦合关系的有力证据。简而言之,这两个发现表明,事实上,在这两种麻醉剂的一个 MAC 剂量期间,血流和代谢是耦合的。他们还间接表明,这些药物产生的新陈代谢差异可能会影响这些药物产生的 CBF 的变化。通过记录同一动物在某些已知增加 CMRglc 的干预前后的血流和新陈代谢,可以更好地检验这一假设,例如癫痫发作。如果 CBF 和 CMRglc 确实是耦合的,人们会看到这两个值同时增加。不幸的是,这一演示更难进行。目前研究中使用的自动摄影方法与这种重复测量方法不兼容,通常的记录 \“全脑 \”CBF 和 CMR [例如,133Xe 冲洗结合动静脉 (A-V) O2 / 血糖比值的差值] 的方法受到以下事实的混淆:CMR 的计算依赖于 CBF 的测量 (这使得 CBF 和 CMR 之间的线性回归比较可疑)。然而,Kuramoto et al (1979) 使用容量测定的 CBF,在呼吸氟烷的狗的外周刺激过程中发现 CBF 和 CMRO2 的平行增加 - 再次支持我们的论点,即在给予临床相关浓度的挥发性麻醉剂期间,血流和新陈代谢仍然紧密耦合。

这一结论具有许多重要的含义。对新皮质 CBF 的研究表明,氟烷比异氟烷有更大的作用 (Todd 和 Drummond,1984;Eintrei 等人,1985;Scheller 等人,1986)。基于这些观察,有人认为氟烷比异氟烷具有更强的直接血管扩张能力 (Shapiro,1986)。然而,在代谢差异最小化 (巴比妥酸盐负荷) 的情况下,比较氟烷和异氟醚麻醉期间的 CBF 表明,这可能不是真的 (Drummond 等,1986)。这个问题也可以在我们目前的研究中得到检验。从图 1 中 CBF 与 CMRglc 的曲线可以看出,异氟烷的曲线高于氟烷的曲线。这表明,在给定的 CMRglc 值下,异氟醚麻醉的动物可能比给予氟烷的动物有更多的流量。这些观察表明,尽管与氟烷麻醉相比,异氟烷对 CMRglc 的总体抑制更大,但异氟烷潜在的更大的血管扩张能力可能解释了先前报道的两种药物相同的半球流量值 (Theye 和 Michenfield,1968;Cucchiara 等人,1974;Stullken 等人,1977)。

在解释我们的结果时,必须评估方法论方面的考虑。首先,我们最初确定 CBF 和 CMRglc 时选择的大脑区与其他人使用的方法有些不同 (这更类似于我们第二次分析中使用的多个斑点样本)。此外,从 8 个标准化的脑切片中提取面积加权的 CMRglc 值来反映整个大脑的价值。然而,选择用于分析的大脑切片是基于这些切片内的皮质下解剖结构,而不是切片之间前后距离的一致性。对我们选定的部分的解剖位置的检查显示,相对偏向于位于中央的部分,而牺牲了更多的吻部和尾部部分。在第二个分析中,一致地选择了 8500 平方像素的单位区域,代表 49 个独立的解剖结构,用于在 8 个脑自显影切片上从相同的解剖位置测定 CBF 和 CMRglc。这些区域被选择来代表大范围的 CMRglc 值,但是相对排除非常低的 CMRglc 值 (白质) 的采样偏差是明显的。纳入更多这些领域可能会改变我们的结果,尽管可能性不大。

其次,血流和代谢研究中的动物在开始测定 CBF 或 CMRglc 之前,麻醉的时间略有不同 (从诱导时间开始,分别为 1 小时 30 分钟和 1 小时 10 分钟)。由于测量 CBF 和 CMRglc 所需的时间不同 (分别为 45s 和 45min),很难为这两项研究建立相同的麻醉暴露时间。然而,大多数 2-DG 的利用发生在 45 分钟测量期的早期 (Sokoloff 等,1977)。因此,选择代谢研究中的麻醉平衡期,以使 CMRglc 测定的中点接近先前 CBF 研究允许的 1 小时 30 分钟的总麻醉暴露时间。结果,CBF 研究组和 CMRglc 研究组的动物接触所研究的麻醉剂的时间略有不同。由于适应麻醉剂产生的血流和新陈代谢变化需要几个小时,与这些微小时差相关的误差预计是最小的 (Warner 等人,1985 年)。

综上所述,1MAC 氟烷和异氟醚麻醉时不同解剖脑结构的 CBF 和 CMRglc 的关系可用两条斜率相等的平行线表示,但 Y 截距不同。这一点,再加上与特定药物相似的 CBF 和 CMRglc 分布模式,是支持 1MAC 麻醉期间完整的血流代谢偶联持续存在的有力证据。此外,在任何给定的 CMRglc 水平,异氟醚麻醉的大鼠都有更大的 CBF 值。这是否表明异氟醚是一种更有效的直接血管扩张剂,或者影响 CBF 的其他因素是否被这些药物差异地改变 (例如,神经元输入) 仍有待确定。这些观察可能在实验中有进一步的应用,在实验中,研究吸入麻醉药的效果时,存在同样确定的 CMR 水平,例如巴比妥酸盐预处理。这些发现也表明,正如 Scheller 等人之前所指出的那样。(1987) 和 Drummond 等人。(1986),麻醉剂对脑血流的影响可能取决于大脑先前存在的代谢状态,在得出关于挥发性药物改变血流的机制的任何结论时,必须考虑代谢活动。

新皮质:额叶、顶叶、颞叶、枕叶在系统发生上出现较晚,称为新皮质,边缘叶发生较早,称为旧皮质。大脑皮质从外到内分为六层:分子层、外颗粒层、锥体细胞层、内颗粒层、节细胞层、多型细胞层,它们由不同类型的神经细胞组成,其中颗粒细胞接受感觉信号,锥体细胞传递运动信息。 ↩︎