低血压对器官灌注和预后的异质性影响

低血压对器官灌注和预后的异质性影响

# 低血压对器官灌注和预后的异质性影响:陈述性综述

Heterogeneous impact of hypotension on organ perfusion and outcomes: a narrative review

Meng L. Heterogeneous impact of hypotension on organ perfusion and outcomes: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127(6):845-861. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2021.06.048

DeepL 翻译 + 人工校对# 摘要

Arterial blood pressure is the driving force for organ perfusion. Although hypotension is common in acute care, there is a lack of accepted criteria for its definition. Most practitioners regard hypotension as undesirable even in situations that pose no immediate threat to life, but hypotension does not always lead to unfavourable outcomes based on experience and evidence. Thus efforts are needed to better understand the causes, consequences, and treatments of hypotension. This narrative review focuses on the heterogeneous underlying pathophysiological bases of hypotension and their impact on organ perfusion and patient outcomes. We propose the iso-pressure curve with hypotension and hypertension zones as a way to visualize changes in blood pressure. We also propose a haemodynamic pyramid and a pressure–output–resistance triangle to facilitate understanding of why hypotension can have different pathophysiological mechanisms and end-organ effects. We emphasise that hypotension does not always lead to organ hypoperfusion; to the contrary, hypotension may preserve or even increase organ perfusion depending on the relative changes in perfusion pressure and regional vascular resistance and the status of blood pressure autoregulation. Evidence from RCTs does not support the notion that a higher arterial blood pressure target always leads to improved outcomes. Management of blood pressure is not about maintaining a prespecified value, but rather involves ensuring organ perfusion without undue stress on the cardiovascular system.

动脉血压是器官灌注的驱动力。尽管低血压在急救中很常见,但对其定义缺乏公认的标准。大多数从业者认为低血压是不良事件,即使是在对生命没有直接威胁的情况下,但根据经验和证据,低血压并不总是导致不良预后,要努力更好地了解低血压的原因、后果和治疗方法。这篇叙述性综述主要关注低血压的异质性基本病理生理学基础及其对器官灌注和患者预后的影响。我们提出了带有低血压和高血压区的等压曲线,作为可视化血压变化的一种方式。我们还提出了血流动力学金字塔和血压 - 心输出量 - 血管阻力三角形,以便于理解为什么低血压会有不同的病理生理机制和对终末器官有不同的影响。我们强调,低血压并不总是导致器官灌注不足;相反,低血压可以保持甚至增加器官灌注,这取决于灌注压和局部血管阻力的相对变化以及血压自动调节的状态。来自 RCT 的证据并不支持较高的动脉血压目标总是改善预后的观点。血压的管理不是为了维持一个预先指定的数值,而是要确保器官的灌注,而不对心血管系统造成不必要的压力。

Keywords: autoregulation, blood pressure, hypotension, organ perfusion, outcome, pathophysiology, perfusion ** 关键词:** 自动调节、血压、低血压、器官灌注、预后、病理生理学、灌注 ::: ::::

Editor's key points

- Hypotension has heterogenous underlying pathophysiological causes and organ-specific effects on tissue perfusion.

- Hypotension does not always lead to organ hypoperfusion; in fact, it may not affect or may even increase organ perfusion.

- The overall evidence from RCTs does not support the notion that a higher blood pressure target always leads to improved patient outcomes.

# 编辑划重点

- 低血压有异质的潜在病理生理学原因和组织灌注的器官特异性效应。

- 低血压并不总是导致器官灌注不足;事实上,它可能不影响甚至可能增加器官灌注。

- RCTs 的总体证据并不支持较高的血压目标总是能改善患者预后的观点。

# 序言

Arterial BP is perhaps the most commonly measured haemodynamic variable. It can increase or decrease acutely to produce hypertension or hypotension, respectively. Although the terms hypertension and hypotension have long been in use, widely accepted criteria defining them in acute care, including in the perioperative, intensive care, and emergency settings, have not been established. This is exemplified by the fact that although the diagnostic criteria for chronic hypertension are defined in chronic care,[[1]],[[2]] although diagnostic criteria have recently been revised,[3]similar clearly defined criteria for acute hypertension in acute care do not exist (but see Sessler and colleagues[4] for recent efforts to establish such criteria). This review focuses on the discussion of acute hypotension, which is a more frequent occurrence than acute hypertension in acute care.

动脉血压可能是最常测量的血流动力学参数。它可以急性增加或减少,分别产生高血压或低血压。尽管高血压和低血压这两个词已经使用了很久,但在急救中,包括围手术期、重症救治和急诊等情形中,广泛接受的定义它们的标准还没有制定出来。这方面实际中的例子是,虽然在慢性病治疗中定义了慢性高血压的诊断标准,[1],[2] 尽管最近修订了诊断标准,[3] 类似的明确定义的急性高血压标准在急救中并不存在(但是,我们见到了 Sessler 及其同事 [4] 最近在努力建立这种标准)。本综述重点讨论急性低血压,因为在急救中低血压比急性高血压更常见。

Hypotension currently lacks widely accepted criteria for diagnosis in acute care.[5],[6] A cohort study showed that both the threshold used to define hypotension and the method chosen to quantify hypotension affect the association between intraoperative hypotension and outcomes.[7] This finding suggests that intraoperative hypotension studies based on different methodologies are not comparable and that it is challenging to apply the reported results in clinical practice. Although hypotension does not always appear to be hazardous based on both clinical experience and available evidence, most practitioners still regard it as undesirable, even in situations that pose no immediate threat to life. This incongruity implies that we may need to reflect on the fundamentals of hypotension, including its underlying pathophysiology and critical impact. Clarification of these fundamentals may improve our understanding of acute hypotension in acute care.

目前,低血压在急救中缺乏广泛接受的诊断标准。[5], [6] 一项队列研究显示,用于定义低血压的阈值和选择量化低血压的方法都会影响术中低血压和预后之间的关联。这一发现表明,基于不同方法的术中低血压研究不具有可比性,把报道中的结果用于临床实践是有问题的。尽管根据临床经验和现有证据,低血压并不总是危险的,但大多数从业者仍然认为低血压是不可取的,即使在没有对生命构成直接威胁的情况下。这种不一致意味着我们可能需要反思低血压的基本原理,包括其基本病理生理学和关键影响。澄清这些基本原理可以改善我们对急性低血压的理解。

# 低血压和预后的队列研究

Hypotension and outcomes based on cohort studies

Most cohort studies show a consistent association between acute hypotension and unfavourable outcomes in acute care.[8],[9] For example cohort studies performed in noncardiac non-neurologic surgical patients show an association between perioperative hypotension and unfavourable outcomes, namely mortality,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] all-cause morbidity,[26] acute kidney injury,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32] myocardial injury,[11],[19],[27],[29],[30],[33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39] congestive heart failure,[40] stroke,[25],[39],[41] cognitive decline,[42] delirium,[43] poor liver[8] and kidney[44] graft function, and post-oesophagectomy leak.[45] However, there are exceptions in which no association between hypotension and unfavourable outcomes was found for noncardiac non-neurologic surgical patients.[46], [47], [48], [49], [50] Similarly, most cohort studies performed in cardiac surgical patients involving cardiopulmonary bypass show an association between perioperative hypotension and increased mortality,[51],[52] major morbidity,[52] watershed stroke,[53] early cognitive dysfunction,[54] postoperative delirium,[55] and acute kidney injury.[56], [57], [58] However, there are exceptions in this patient population as well: one study failed to associate hypotension with postoperative delirium,[59] and three studies failed to associate hypotension with acute kidney injury.[60], [61], [62]

大多数队列研究显示,急性低血压与急救的不良预后之间存在一致的联系。例如,在非心脏非神经外科病人中进行的队列研究显示,围手术期低血压与不良的预后,即死亡率,[10], [11], [12] 之间有关联。[13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] 全因发病率,[26] 急性肾损伤,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32] 心肌损伤,[11], [19] 。 [27],[29],[30],[33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39] 充血性心力衰竭,[40] 卒中,[25],[39],[41] 认知能力下降,[42] 精神错乱,[43] 肝[8 ] 和肾[44 ] 移植物功能不佳,以及食管切除术后渗漏。 [45] 然而,也有例外情况,在非心脏非神经系统手术患者中没有发现低血压与不良预后之间的关联。[46], [47], [48], [49], [50] 同样,在涉及体外循环的心脏手术患者中进行的大多数队列研究显示,围手术期低血压与死亡率增加、[51] 、[52] 主要发病率、[52] 分水岭卒中、[53] 早期认知功能障碍、[54] 术后谵妄和急性肾损伤之间存在关联。 [56], [57], [58] 然而,在这个病人群体中也有例外:一项研究未能将低血压与术后谵妄联系起来,[59] ,三项研究未能将低血压与急性肾损伤联系起来。[60], [61], [62]

The results of these cohort studies should be interpreted in light of their inherent limitations. The first limitation is related to the variety of thresholds used to define hypotension and the methods chosen to quantify the accumulative effects of hypotension (i.e. the exposure).[5],[7] The variety in exposure definitions affects the results of the association between intraoperative hypotension and outcomes.[7] Moreover, the baseline BP used in retrospective studies might be unreliable as BP has a circadian fluctuation[63] and also tends to be higher in clinical/hospital settings (white coat hypertension).[64] The second limitation is related to the definition of outcomes. The outcomes, defined retrospectively, were not pre-specified, leading to variations in the timing, criteria, validity, relevance, and availability of the different outcome measures. The third limitation is related to confounder control. Hypotension has different underlying pathophysiological causes and effects on organ perfusion (see below), and organ perfusion, not the blood pressure per se, determines outcomes relevant to haemodynamics. Cohort studies investigating intraoperative hypotension do not normally consider flow/perfusion-related information (owing to the lack of routine measurement); therefore, these studies could be confounded by this unmeasured yet critical information. How hypotension is treated could also confound cohort studies because different treatments, although they may all increase BP, may have different effects on organ perfusion and other variables.[65]

解释这些队列研究的结果时,应考虑到其固有的局限性。第一个局限性与用于定义低血压的各种阈值以及用于量化低血压累积效应(即暴露)的方法有关。[5], [7] 暴露定义的多样性影响了术中低血压和预后之间的关联结果。[7] 。此外,回顾性研究中使用的基线血压可能不可靠,因为血压有昼夜波动[63] ,而且在临床 / 医院环境中往往较高(白大衣高血压)[64] 。第二个限制是与预后的定义有关。预后的定义是回顾性的,没有预先指定,导致不同预后测量的时间、标准、有效性、相关性和可用性的变化。第三个限制与混杂因素控制有关。低血压有不同的潜在病理生理原因和对器官灌注的影响(见下文),器官灌注,而不是血压本身,决定了与血流动力学相关的预后。调查术中低血压的队列研究通常不考虑与血流 / 灌注有关的信息(由于缺乏常规测量);因此,这些研究可能会被这种未测量的关键信息所混淆。如何治疗低血压也可能混淆队列研究,因为不同的治疗方法虽然都可能增加血压,但对器官灌注和其他参数可能有不同的影响。[65]

# 低血压和预后的随机对照试验

Hypotension and outcomes based on randomised controlled trials

Among studies investigating the relationship between hypotension and outcomes, there is a conspicuous discrepancy between evidence based on cohort studies and evidence based on RCTs. Although an abundance of cohort studies have suggested an association between perioperative hypotension and unfavourable outcomes,[4] RCTs have failed to demonstrate consistently improved outcomes from maintaining a higher BP ([Table 1]).[66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73] Assessing this body of evidence in surgical patients is limited by: (1) different surgeries, (2) different BP targets and different BP-related interventions, (3) different outcome measures, and (4) different flow/perfusion (including pump flow during cardiopulmonary bypass). In patients with septic shock requiring resuscitation, there was no significant difference in mortality between strategies targeting a higher (80–85 mmHg) or lower (65–70 mmHg) MAP.[74] In critically ill older patients with vasodilatory hypotension, there was no significant difference in mortality between permissive hypotension (targeting an MAP of 60–65 mmHg) and usual care (targeting a higher BP).[75] These inconsistent findings, albeit likely to have multifactorial causes, suggest that we may need an improved approach toward understanding hypotension, including its definition, pathophysiology, and effects on organ perfusion and patient outcomes, in acute care. In other words, BP management is not as simple as merely targeting a prespecified BP value.

在调查低血压和预后之间关系的研究中,基于队列研究的证据和基于 RC 证据之间存在明显的差异。尽管大量的队列研究表明围术期低血压与不良预后之间存在关联,[4] RCT 能证明维持高血压可以持续改善预后([表 1])。[66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73] 评估外科病人的这组证据受到以下限制。(1) 不同的手术,(2) 不同的血压目标和不同的血压相关干预,(3) 不同的预后测量,以及 (4) 不同的流量 / 灌注(包括体外循环期间的泵流量)。在需要复苏的脓毒症休克患者中,以较高(80-85 mmHg )或较低(65-70 mmHg )的 MA 目标的策略在死亡率方面没有明显差异。[74] 。在血管扩张性低血压的老年危重病人中,允许性低血压(以 60-65 mmHg 为目标)和常规救治(以较高的血压为目标)之间的死亡率没有明显差异。这些不一致的发现,尽管可能有多因素的原因,但表明我们可能需要改进对低血压的理解,包括其定义、病理生理学以及对器官灌注和病人预后的影响,在急救中。换句话说,血压管理并不像仅仅针对一个预先指定的血压值那么简单。

Table 1 RCTs comparing a higher BP target with a lower BP target in perioperative care. ∗Early termination. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; DWI, diffusion-weighed magnetic resonance imaging.

| Year (Authors) | Surgery | Patients (n) | Higher BP target | Lower BP target | Outcomes | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Noncardiac surgery* | ||||||

| 1999 (Williams-Russo and colleagues)[73] | Hip surgery under epidural anaesthesia | 235 | MAP=55–70 mmHg | MAP=45–55 mmHg | Cognitive, cardiac and renal complications | No difference |

| 2016 (Carrick and colleagues)[66] ,∗ | Laparotomy or thoracotomy for trauma | 168 | MAP=65 mmHg | MAP=50 mmHg | 30 day mortality | No difference |

| 2017 (Futier and colleagues)[67] | Major abdominal surgery | 292 | SBP=90–110% of resting value | SBP >80 mmHg or 60% of resting value | A composite of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ dysfunction by day 7 after surgery | A higher BP target is beneficial |

| *Cardiac surgery* | ||||||

| 1995 (Gold and colleagues)[68] | CABG with CPB | 248 | MAP=80–100 mmHg during CPB | MAP=50–60 mmHg during CPB | Mortality, cardiac, neurologic, and cognitive complications, and changes in quality of life | A higher MAP during CPB is beneficial |

| 2007 (Charlson and colleagues)[70] | CABG with CPB | 412 | MAP target=80 mmHg during CPB | MAP target=pre-bypass level during CPB | Mortality, major neurologic or cardiac complications, cognitive complications or deterioration in functional status | No difference |

| 2011 (Siepe and colleagues)[69] | CABG with CPB | 92 | MAP=80–90 mmHg during CPB | MAP=60–70 mmHg during CPB | Early postoperative cognitive dysfunction and delirium | A higher MAP during CPB is beneficial |

| 2014 (Azau and colleagues)[71] | Cardiac surgery with CPB | 300 | MAP=75–85 mmHg during CPB | MAP=50–60 mmHg during CPB | Acute kidney injury | No difference |

| 2018 (Vedel and colleagues)[72] | Cardiac surgery with CPB | 197 | MAP=70–80 mmHg during CPB | MAP=40–50 mmHg during CPB | Cerebral infarcts detected by DWI | No difference |

表 1 在围手术期治疗中比较较高血压目标和较低血压目标的 RCTs。∗ 早期终止。CABG,冠状动脉旁路移植;CPB,体外循环;DWI,弥散加权磁共振成像。

| 年(作者) | 手术 | 患者 (n) | 较高的 BP 目标 | 较低的 BP 目标 | 预后 | 结论 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 非心脏手术 | ||||||

| 1999 (Williams-Russo and colleagues)[73] | 硬膜外麻醉下髋关节手术 | 235 | MAP=55–70 mmHg | MAP=45–55 mmHg | 认知、心脏和肾脏并发症 | 无差异 |

| 2016 (Carrick and colleagues)[66] ,∗ | 因创伤行剖腹手术或开胸手术 | 168 | MAP=65 mmHg | MAP=50 mmHg | 30 天死亡率 | 无差异 |

| 2017 (Futier and colleagues)[67] | 腹部大手术 | 292 | SBP=90–110% 静息值 | SBP >80 mmHg or 60% 静息值 | 术后第 7 天的全身炎症反应综合征和器官功能障碍的复合终点 | 较高的血压目标是有益的 |

| 心脏手术 | ||||||

| 1995 (Gold and colleagues)[68] | 体外循环下心脏搭桥 | 248 | MAP=80–100 mmHg during CPB | MAP=50–60 mmHg during CPB | 死亡率、心脏、神经和认知并发症,和生活质量的变化 | CPB 期间较高的 MAP 是有益的 |

| 2007 (Charlson and colleagues)[70] | 体外循环下心脏搭桥 | 412 | MAP target=80 mmHg during CPB | MAP target=pre-bypass level during CPB | 死亡率,主要神经或心脏并发症,认知并发症或功能状态恶化 | 无差异 |

| 2011 (Siepe and colleagues)[69] | 体外循环下心脏搭桥 | 92 | MAP=80–90 mmHg during CPB | MAP=60–70 mmHg during CPB | 术后早期认知功能障碍和谵妄 | CPB 期间较高的 MAP 有益 |

| 2014 (Azau and colleagues)[71] | 体外循环下心脏手术 | 300 | MAP=75–85 mmHg during CPB | MAP=50–60 mmHg during CPB | 急性肾损伤 | 无差异 |

| 2018 (Vedel and colleagues)[72] | 体外循环下心脏手术 | 197 | MAP=70–80 mmHg during CPB | MAP=40–50 mmHg during CPB | DWI 检测脑梗死 | 无差异 |

# 血压的性质

Nature of blood pressure

Understanding the nature of BP helps to clarify when and why hypotension is worrisome. BP is the force exerted by the circulating blood that propels blood through the tissues and organs, that is organ perfusion, especially to the brain because it is at a higher level relative to the heart in sitting or standing individuals. Higher BP is required for the increased height difference between the brain and heart, as illustrated by the remarkably different baseline BP between standing giraffes and humans (systolic BP, ~300 vs ~120 mmHg).[76]

了解血压的性质有助于阐明何时以及为何低血压令人担忧。血压是血液循环施加的力量,推动血液通过组织和器官,也就是器官灌注,特别是大脑,因为在坐着或站着的人,它相对于心脏处于较高的水平。大脑和心脏之间的高度差增加,需要更高的血压,正如站立的长颈鹿和人类之间明显不同的基线血压(收缩压,~300 vs ~120 mmHg )所示的那样。[76]

# 低血压具有不同的基本病理生理机制

Hypotension has different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms

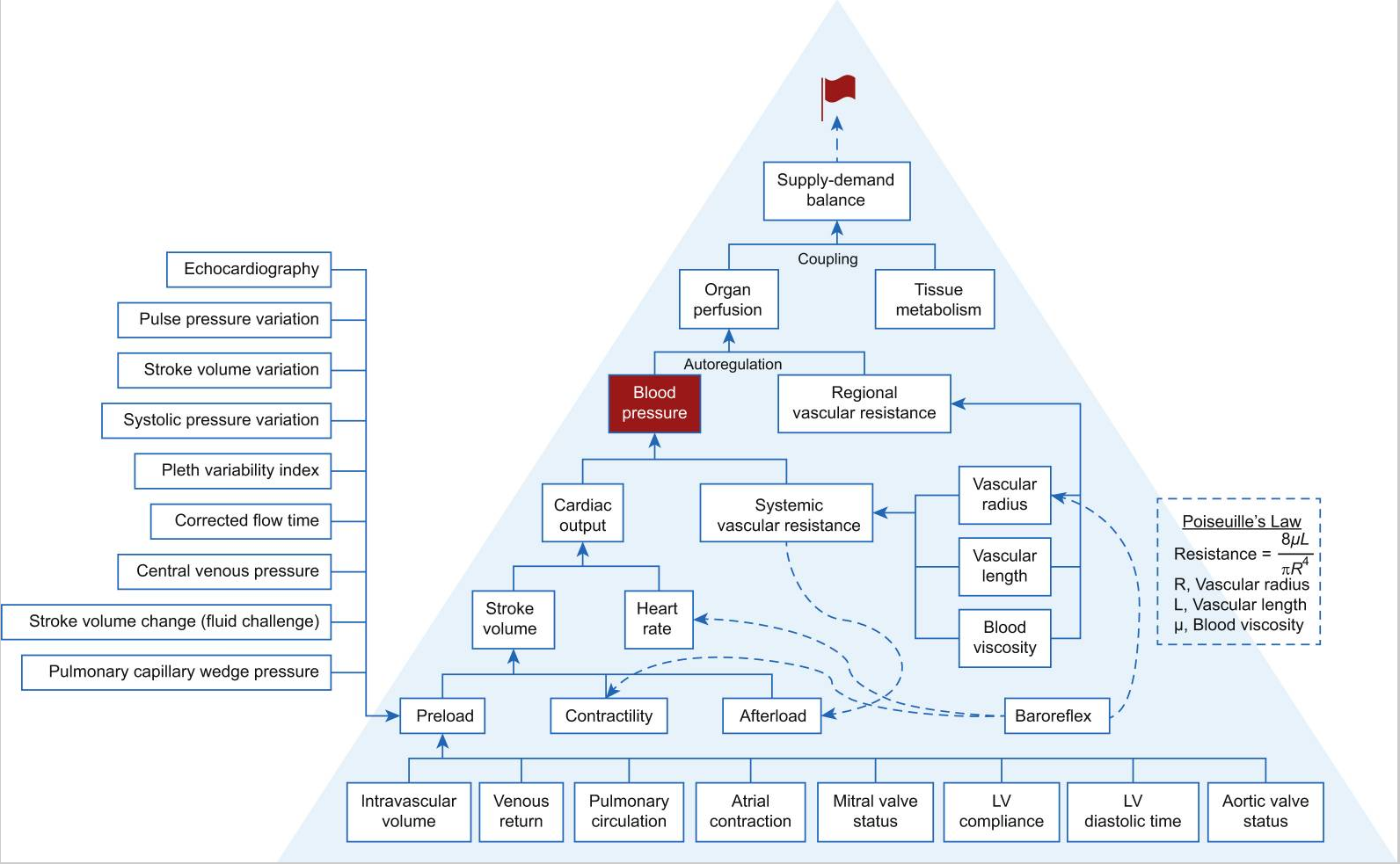

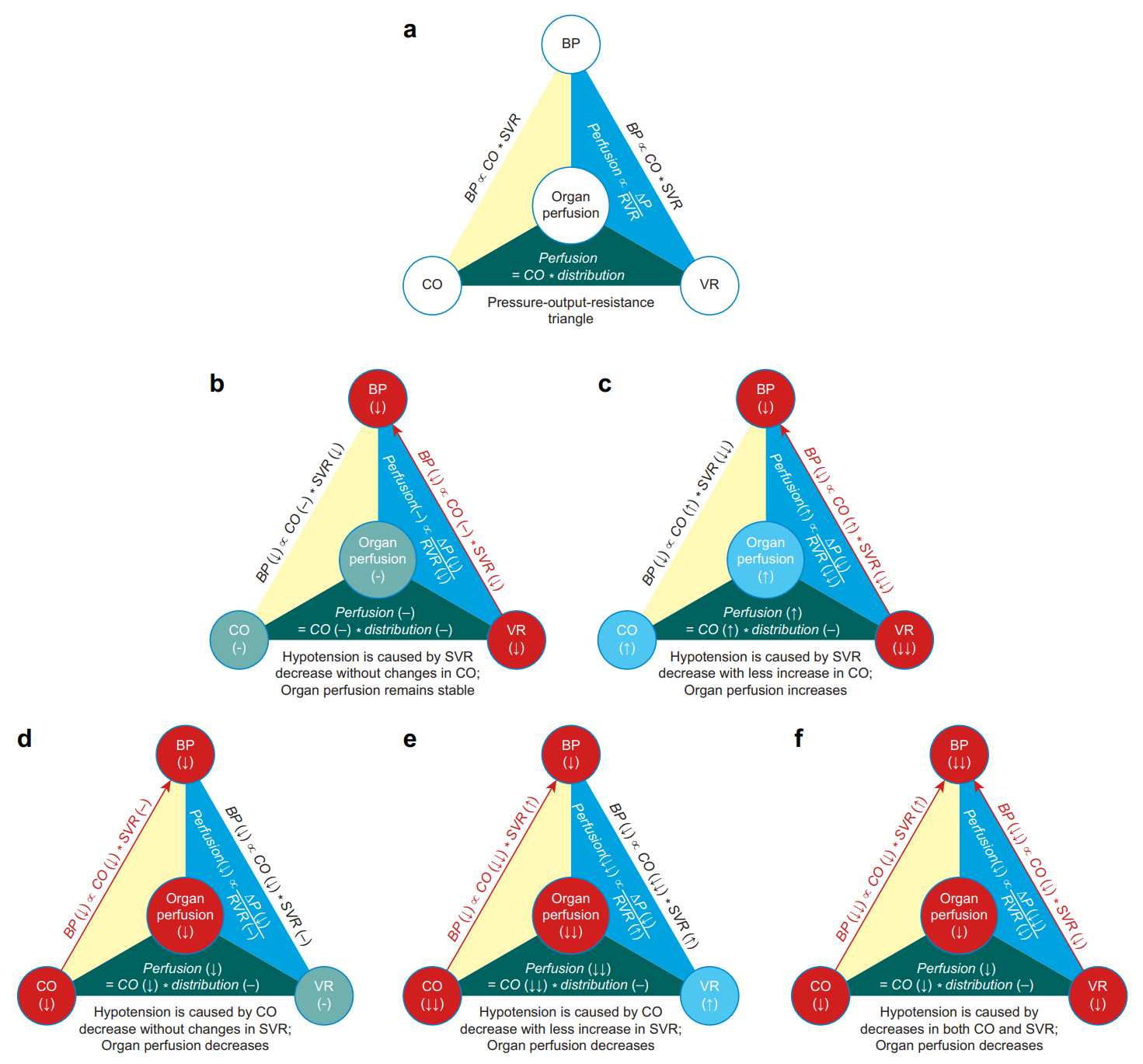

Arterial blood pressure is the result of multiple haemodynamic elements (Fig. 1).[77] Therefore, hypotension is not always equivalent because it can have different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms as a result of different combinations of changes in relevant factors. The variety of potential underlying pathophysiological mechanisms based on the haemodynamic pyramid framework is presented in [Figure 1]. However, we use a simpler pressure–output–resistance triangle framework that regards BP as the product of cardiac output (CO) and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (Fig. 2a).

动脉血压是多种血流动力学要素的结果(图 1)。[77] 因此,低血压并不总是等价的,因为它可以有不同的潜在病理生理机制,这是相关因素变化的不同组合的结果。基于血流动力学金字塔框架的各种潜在的病理生理学机制在图 1 中提出。然而,我们使用更简单的血压 - 心输出量 - 血管阻力三角框架,将血压视为心输出量(CO)和全身血管阻力(SVR)的产物(图 2a)。

Fig. 1. Haemodynamic pyramid. Venous blood must return to the heart and flow through the right heart, pulmonary vasculature, left atrium, and mitral valve to create the preload of the left ventricle. The magnitude of left ventricle preload is also dependent on atrial contraction, mitral valve status, aortic valve status (e.g. aortic valve regurgitation leading to augmented preload), and the compliance and diastolic time of the left ventricle. The magnitude of stroke volume is dependent on preload, myocardial contractility, and afterload. Blood pressure is dependent on cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance (SVR), whereas cardiac output is the product of stroke volume and heart rate. Afterload and SVR are related. SVR is proportional to the vascular length and blood viscosity and inversely proportional to vascular radius to the fourth power, a relationship described by the Hagen–Poiseuille equation. Organ perfusion is dependent on blood pressure (or perfusion pressure) and regional vascular resistance (RVR). The relationship between organ perfusion pressure and RVR is governed by pressure autoregulation. The match between organ perfusion and tissue metabolic activity determines perfusion adequacy and is one of the premises of organ well-being. Adequate organ perfusion is the primary goal of haemodynamic management. Baroreflex exerts its effects primarily on the vascular radius, heart rate, and myocardial contractility. Blood pressure (highlighted in red fonts) and heart rate are always monitored in acute care. The modern haemodynamic monitor enables the assessment of stroke volume and thus cardiac output or index. Tissue oximetry based on near-infrared spectroscopy enables assessing the balance between tissue oxygen consumption and supply. A variety of means and parameters assesses preload. Modern haemodynamic management has a variety of approaches with likely different effectiveness depending on the outcomes of interest.[77], [78], [79] LV, left ventricle.

图. 1. 血流动力学金字塔。静脉血必须返回心脏,流经右心、肺血管、左心房和二尖瓣,以形成左心室的前负荷。左心室前负荷的大小还取决于心房收缩、二尖瓣状态、主动脉瓣状态(如主动脉瓣反流导致前负荷增加)以及左心室的顺应性和舒张时间。每搏量的大小取决于前负荷、心肌收缩力和后负荷。血压取决于心输出量和全身血管阻力(SVR),而心输出量是每搏量和心率的乘积。后负荷和 SVR 是相关的。SVR 与血管长度和血液粘度成正比,与血管半径的四次方成反比,这种关系由哈根 - 泊肃叶方程描述。器官灌注取决于血压(或灌注压)和局部血管阻力(RVR)。器官灌注压力和 RVR 之间的关系受压力自动调节的制约。器官灌注和组织代谢活动之间的匹配决定了灌注的充分性,是器官健康的前提之一。充分的器官灌注是血流动力学管理的首要目标。压力反射主要对血管半径、心率和心肌收缩力产生影响。血压(红色字体突出)和心率在急救中总是被监测。现代血流动力学监测仪可以评估每搏量,从而评估心输出量或指数。基于近红外光谱的组织血氧仪可以评估组织耗氧和供氧之间的平衡。各种各样的手段和参数可以评估前负荷。现代血流动力学管理有多种方法,根据所关注的结果可能有不同的效果。[77], [78], [79]

LV,左心室。

Fig. 2. The pressure–output–resistance triangle. Organ perfusion is in the centre of the triangle. This diagram is based on the following premises: (1) changes in systemic vascular resistance (determinant of blood pressure) and regional vascular resistance (determinant of organ perfusion) are concordant, and (2) the share of cardiac output among various organs remains stable. Blood pressure is proportional to cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance. Organ perfusion is proportional to perfusion pressure and inversely proportional to regional vascular resistance; it is also a percentage share of cardiac output (a). Hypotension can be caused by a decrease in systemic vascular resistance (close red circle and red arrow), and in this case, organ perfusion remains stable because of the proportional decreases in blood pressure and regional vascular resistance (b). Hypotension can be caused by a significant decrease in systemic vascular resistance (closed red circle and red arrow), although there is a lesser degree of increase in cardiac output (closed blue circle). In this case, organ perfusion is increased because of the lesser decrease in blood pressure than the decrease in regional vascular resistance (c). Hypotension can be caused by a decrease in cardiac output (closed red circle and red arrow), and in this case, organ perfusion is decreased because of decreased perfusion pressure in the face of an unchanged regional vascular resistance (d). Hypotension can be caused by a significant decrease in cardiac output (closed red circle and red arrow), although there is a lesser degree of increase in systemic vascular resistance (closed blue circle). In this case, organ perfusion has a significant decrease because of decreased perfusion pressure in the face of an increased regional vascular resistance (e). Hypotension can be caused by simultaneous decreases in cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance (closed red circles and red arrows). In this case, organ perfusion is decreased because of the more significant decrease in perfusion pressure than the decrease in regional vascular resistance (f). CO, cardiac output; VR, vascular resistance which can be either SVR (systemic vascular resistance) or RVR (regional vascular resistance) depending on the context; ΔP, perfusion pressure.

图. 2. 血压 - 心输出量 - 血管阻力三角形。器官灌注位于三角形的中心位置。此图基于以下前提:(1)全身血管阻力(血压的决定因素)和局部血管阻力(器官灌注的决定因素)的变化是一致的,(2)心输出量在各器官中的份额保持稳定。血压与心输出量和全身血管阻力成正比。器官灌注与灌注压成正比,与局部血管阻力成反比;它也是心输出量的一个百分比份额(a)。低血压可由全身血管阻力下降引起(接近红圈和红色箭头),在这种情况下,器官灌注保持稳定,因为血压和局部血管阻力的比例下降(b)。低血压可由全身血管阻力的显著下降引起(闭合的红圈和红色箭头),尽管心输出量有较小程度的增加(闭合的蓝圈)。在这种情况下,由于血压的降低比局部血管阻力的降低要小,所以器官灌注量增加(c)。低血压可由心输出量减少引起(封闭的红圈和红色箭头),在这种情况下,器官灌注量减少,因为在局部血管阻力不变的情况下,灌注压力下降(d)。低血压可由心输出量的明显减少引起(封闭的红圈和红色箭头),尽管全身血管阻力的增加程度较小(封闭的蓝圈)。在这种情况下,由于在局部血管阻力增加的情况下灌注压力下降,器官灌注明显减少(e)。低血压可由心输出量和全身血管阻力的同时下降引起(封闭的红圈和红色箭头)。在这种情况下,由于灌注压的下降比局部血管阻力的下降更明显,所以器官灌注减少(f)。

CO,心输出量;VR,血管阻力,根据情况可以是 SVR(全身血管阻力)或 RVR(局部血管阻力);ΔP,灌注压。

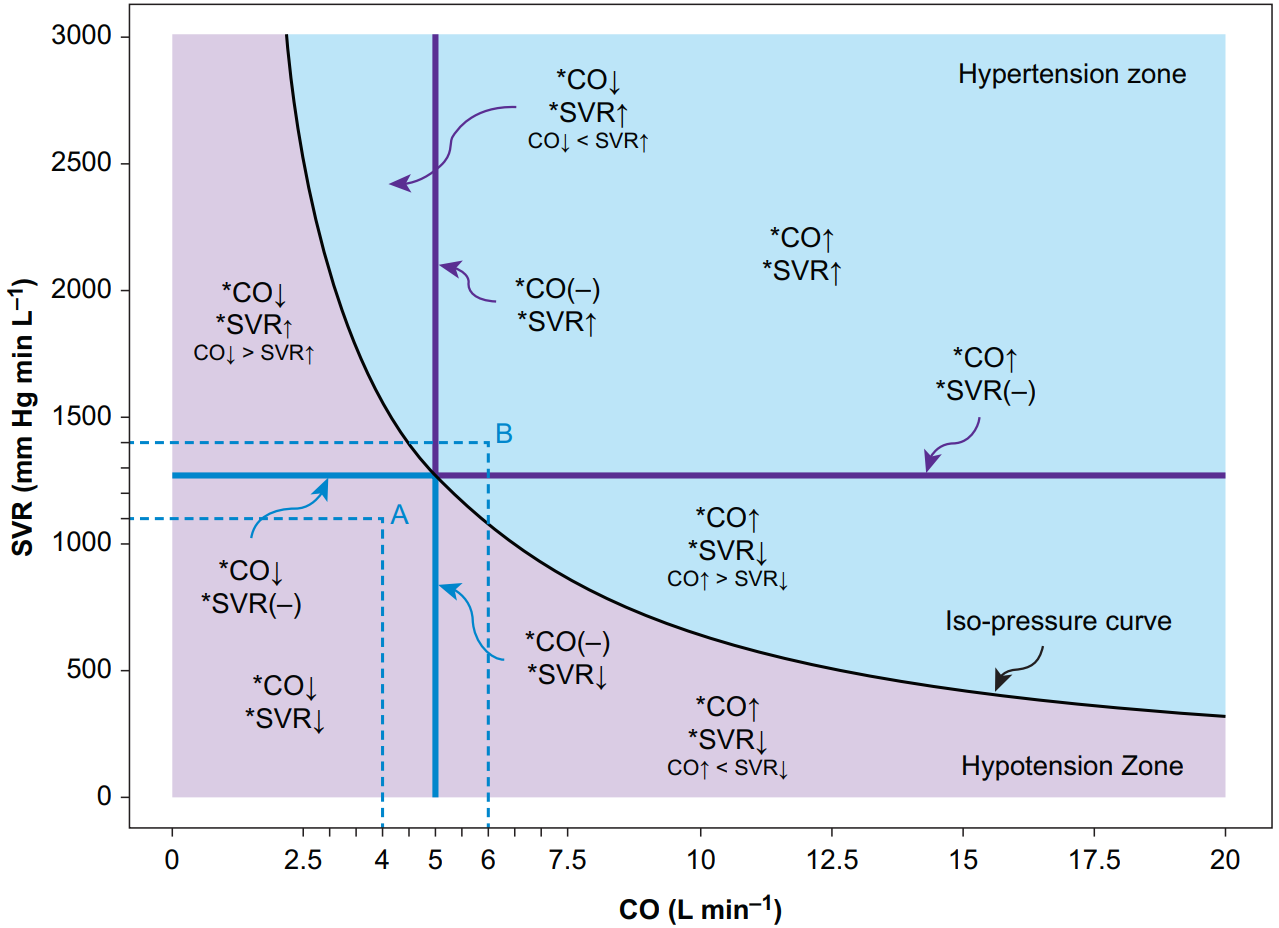

BP is determined primarily by stroke volume (or CO) and SVR at a given filling pressure, for example central venous pressure (CVP); the relationship among these variables is governed by the equation CO×SVR=(MAP−CVP)×80 (Fig. 3).[80] Thus BP can be the same for different CO and SVR values as long as the CO-SVR products are the same. For a constant CO-SVR product, the curve formed by different CO and SVR pairs (with different values) is referred to here as the iso-pressure curve (Fig. 3). The areas below and above the iso-pressure curve are referred to as the hypotension and hypertension zones, respectively (Fig. 3). The concepts of the iso-pressure curve and the hypotension and hypertension zones are explained in [Figure 3]. Hypotension has the following five exclusive underlying pathophysiological mechanisms based on different changes in CO and SVR ([Fig 2], [Fig 3]):

血压主要由给定充盈压下的每搏量(或 CO)和 SVR 决定,例如中心静脉压(CVP);这些参数之间的关系受方程式 CO×SVR=(MAP-CVP)×80(图 3(#fig3))。[80] 。因此,只要 CO-SVR 的乘积相同,不同的 CO 和 SVR 值,BP 就可以相同。对于一个恒定的 CO-SVR 乘积,由不同的成对的 CO 和 SVR(不同的值)形成的曲线在这里被称为等压曲线(图 3)。等压曲线下方和上方的区域分别被称为低血压区和高血压区(图 3)。图 3 中解释了等压线以及低血压和高血压区的概念。基于 CO 和 SVR 的不同变化,低血压有以下五种独有的基本病理生理机制(图 2,图 3):

SVR decreases whereas CO remains stable (Fig. 2b). SVR decreases whereas CO increases, but the effect of the SVR decrease exceeds the effect of the CO increase (Fig. 2c). CO decreases whereas SVR remains stable (Fig. 2d). CO decreases whereas SVR increases, but the effect of the CO decrease surpasses the effect of the SVR increase (Fig. 2e). Both CO and SVR decrease (Fig. 2f).

SVR 下降而 CO 保持稳定(图 2b)。SVR 下降而 CO 增加,但 SVR 下降的影响超过了 CO 增加的影响(图 2c)。CO 减少,而 SVR 保持稳定(图 2d)。CO 减少而 SVR 增加,但是 CO 减少的效果超过了 SVR 增加的效果(图 2e)。CO 和 SVR 都下降(图 2f)。

Fig. 3. Hypotension and hypertension zones divided by the iso-pressure curve. The abscissa indicates CO, and the ordinate indicates SVR. The following equation governs the relationship among different systemic haemodynamic variables: CO×SVR=(MAP−CVP)×80. The black curve is the iso-pressure curve; for a given pair of CO and SVR values, as long as the CO–SVR product equals the difference of MAP and CVP times 80, the point determined by the CO–SVR pair falls on the iso-pressure curve. In this case, we assume MAP is 85 mmHg and the CVP is 5 mmHg to exemplify the concept; the point representing a CO of 5 L min−1 and an SVR of 1280 mmHg min L−1 falls on the black iso-pressure curve because the CO-SVR product equals the MAP–CVP difference times 80. The left lower purple area is called the hypotension zone because any point in this area, no matter what CO and SVR values it presents, leads to a smaller MAP–CVP difference than the MAP-CVP difference dictating the iso-pressure curve. For example, point A, determined by a CO of 4 L min−1 and an SVR of 1100 mmHg min L−1, corresponds to a MAP–CVP difference of approximately 55 mmHg; if assuming CVP equals 5 mmHg, MAP is 60 mmHg in this example. The combinations of different CO and SVR changes represent different underlying pathophysiologies of hypotension. The right upper blue area is called the hypertension zone because any point in this area, no matter what CO and SVR values it represents, leads to a larger MAP–CVP difference than the MAP–CVP difference dictating the iso-pressure curve. For example, point B, determined by a CO of 6 L min−1 and an SVR of 1400 mmHg min L−1, corresponds to a MAP–CVP difference of approximately 105 mmHg; if assuming CVP equals 5 mmHg, the MAP is 110 mmHg in this example. The combinations of different CO and SVR changes represent different underlying pathophysiologies of hypertension.

CO, cardiac output; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; CVP, central venous pressure.

图. 3. 低血压和高血压区按等压曲线划分。横轴表示 CO,纵轴表示 SVR。下面的公式制约着不同系统血流动力学参数之间的关系。CO×SVR=(MAP-CVP)×80。黑色曲线是等压曲线;对于给定的一对 CO 和 SVR 值,只要 CO-SVR 的乘积等于 MAP 和 CVP 之差乘以 80,由成对 CO-SVR 决定的点就落在等压曲线上。在这种情况下,我们假设 MAP 为 85 mmHg ,CVP 为 5 mmHg 来说明这一概念;代表 5 L min−1 的 CO 和 1280 mmHg min L−1 的 SVR 的点落在黑色等压线上,因为 CO-SVR 的乘积等于 MAP-CVP 之差乘以 80。左下角的紫色区域被称为低血压区,因为这个区域的任何一点,无论它呈现什么样的 CO 和 SVR 值,都会导致 MAP-CVP 的差值小于决定等压曲线的 MAP-CVP 的差值。例如,由 4 L min-1 的 CO 和 1100 mmHg min L-1 的 SVR 决定的 A 点,对应的 MAP-CVP 差值约为 55 mmHg;如果假设 CVP 等于 5 mmHg,本例中 MAP 为 60 mmHg。不同的 CO 和 SVR 变化的组合代表了低血压的不同潜在病理生理学。右上方的蓝色区域被称为高血压区,因为该区域的任何一点,无论它代表什么 CO 和 SVR 值,都会导致 MAP-CVP 的差值大于支配等压曲线的 MAP-CVP 的差值。例如,由 6 L min-1 的 CO 和 1400 mmHg min L-1 的 SVR 决定的 B 点,对应的 MAP-CVP 差值约为 105 mmHg;如果假设 CVP 等于 5 mmHg,在这个例子中 MAP 为 110 mmHg。不同的 CO 和 SVR 变化的组合代表了高血压的不同潜在病理生理学。

CO,心输出量;SVR,全身血管阻力;CVP,中心静脉压。

Although each of these mechanisms leads to hypotension, they have different impacts on organ perfusion, as discussed in the following section.

尽管这些机制中的每一个都会导致低血压,但它们对器官灌注的影响是不同的,这一点将在下一节讨论。

This simplified approach should not distract our attention from the causes of changes in CO and SVR as they themselves have different determinants (Fig. 1). CO is the product of HR and stroke volume (SV), with SV dependent on preload, myocardial contractility, and afterload. SVR is determined by the vascular radius, vascular length, and blood viscosity. Clinically, interventions such as the administration of vasopressors,[65] beta-adrenergic antagonists,[81] and calcium channel blockers[82] and the use of pacemakers,[83] can lead to changes in these haemodynamic aspects, and therefore BP changes.

这种简化方法不应分散我们对 CO 和 SVR 变化原因的注意力,因为它们本身有不同的决定因素(图 1)。CO 是心率和每搏量(SV)的乘积,SV 取决于前负荷、心肌收缩力和后负荷。SVR 由血管半径、血管长度和血液粘稠度决定。在临床上,干预措施如给予血管抑制剂、[65] β- 肾上腺素能拮抗剂、[81] 和钙通道阻滞剂[82] 以及使用起搏器、[83] 可导致这些血流动力学方面的变化,从而导致血压变化。

# 低血压对灌注的器官特异性影响

Organ-specific impact of hypotension on perfusion

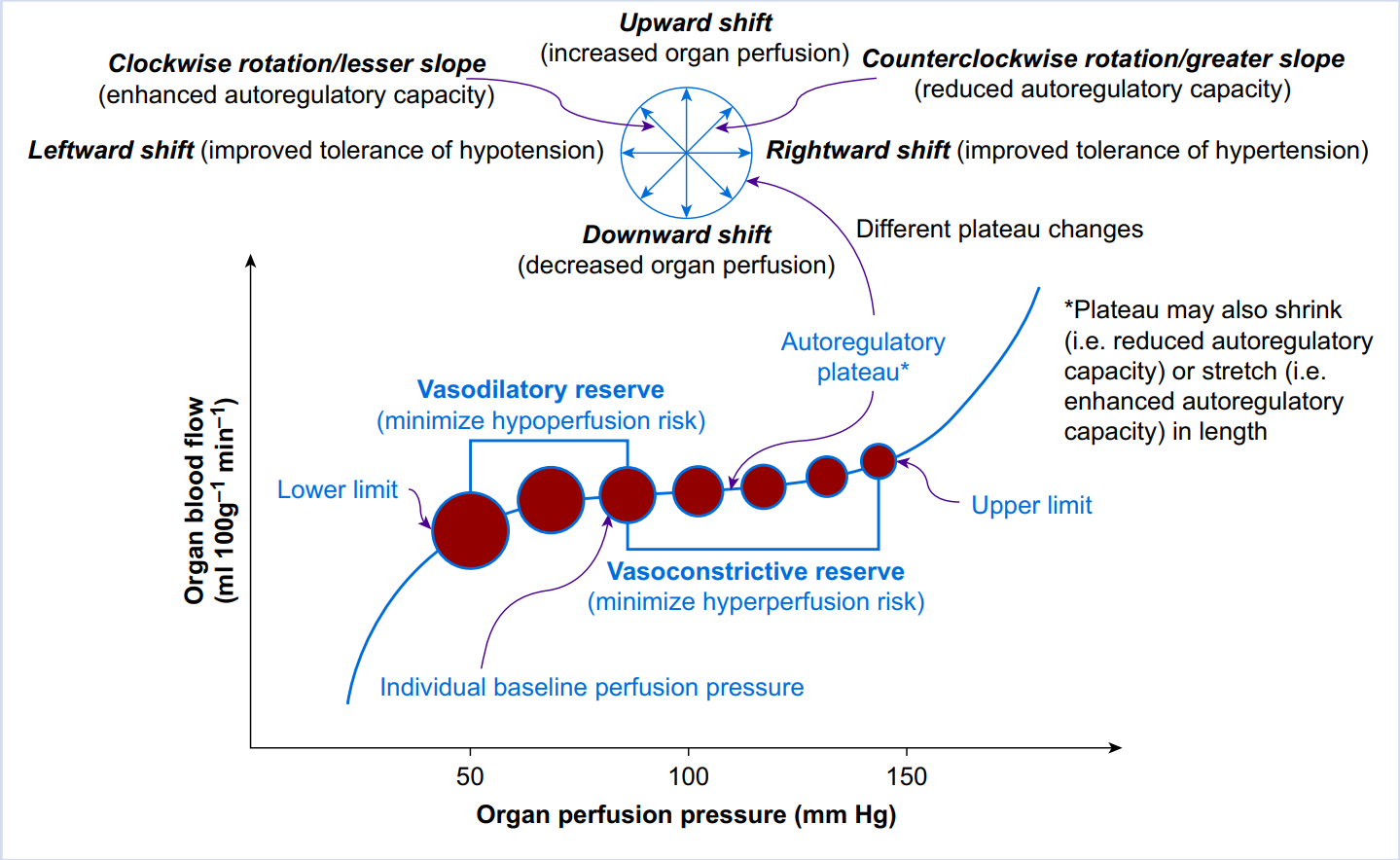

Hypotension, although usually leading to decreased perfusion pressure, does not always lead to organ hypoperfusion because organ perfusion is determined by the perfusion pressure divided by the regional vascular resistance (RVR). Based on Poiseuille's law, RVR is determined by the vascular radius, vascular length, and blood viscosity, although the vascular length rarely changes clinically. Multiple factors can change the vascular radius or vasomotor tone, for example age, atherosclerosis, blood pressure, hypercapnia, and vasoactive drugs (to name a few), and thus lead to RVR changes. The change in vasomotor tone secondary to a change in perfusion pressure is mediated by the myogenic mechanism and is the foundation of the pressure-dependent autoregulation of organ blood flow (Fig. 4). Depending on the relative direction and magnitude of changes in RVR as compared with perfusion pressure, hypotension can have the following three effects on organ perfusion:

- Organ perfusion remains stable if the effects of the decreases in perfusion pressure and RVR are comparable, a scenario in which the underlying pathophysiology of hypotension is an SVR decrease without changes in CO (Fig. 2b). This impact is consistent with the conventional concept of pressure autoregulation, as discussed in the following section.

- Organ perfusion increases if the effect of the perfusion pressure decrease is less than that of the RVR decrease, a scenario in which hypotension is secondary to an SVR decrease accompanied by a lesser degree of CO increase (Fig. 2c), as exemplified by the use of certain calcium channel blockers.[82]

- Organ perfusion decreases if perfusion pressure decreases in the face of one of the following changes in RVR: (1) an unchanged RVR – that is a scenario in which the underlying pathophysiology of hypotension is a CO decrease without changes in SVR (Fig. 2d); (2) an increased RVR – that is a scenario in which hypotension is secondary to a CO decrease accompanied by a lesser degree of SVR increase (Fig. 2e); or (3) a decreased RVR, with the degree of the RVR decrease less than that of the perfusion pressure decrease – a scenario in which hypotension is secondary to a decrease in both CO and SVR (Fig. 2f).

低血压虽然通常导致灌注压下降,但并不总是导致器官灌注不足,因为器官灌注是由灌注压除以局部血管阻力(RVR)决定的。根据泊肃叶定律,RVR 由血管半径、血管长度和血液粘度决定,尽管血管长度在临床上很少变化。多种因素可以改变血管半径或血管运动张力,例如年龄、动脉硬化、血压、高碳酸血症和血管活性药物(仅举几例),从而导致 RVR 变化。继发于灌注压变化的血管运动张力的变化是由肌源性机制介导的,是器官血流的压力依赖性自动调节的基础(图 4)。根据 RVR 与灌注压变化的相对方向和幅度,低血压对器官灌注可产生以下三种影响:

- 如果灌注压和 RVR 下降的影响相当,则器官灌注保持稳定,这种情况下,低血压的基本病理生理学是 SVR 下降而 CO 没有变化(图 2b)。这种影响与压力自动调节的传统概念是一致的,这一点将在下一节讨论。

- 如果灌注压下降的影响小于 RVR 下降的影响,则器官灌注量会增加,这种情况下,低血压是继发于 SVR 下降而伴随着较小程度的 CO 增加(图 2c),如使用某些钙通道阻断剂的例子。

- 如果在 RVR 出现以下变化时,灌注压力下降,则器官灌注会减少:(1)RVR 不变 -- 即低血压的基本病理生理学是 CO 下降而 SVR 没有变化的情况(图 2d);(2)RVR 增加 -- 即低血压继发于 CO 下降,同时伴有较小程度的 SVR 增加(图 2e);或(3)RVR 下降,但 RVR 下降的程度小于灌注压下降的程度 -- 即低血压继发于 CO 和 SVR 下降的情况(图 2f)。

Fig. 4. Pressure autoregulation of organ perfusion. The abscissa represents organ perfusion pressure whereas the ordinate represents organ blood flow. The relationship between organ perfusion pressure and blood flow is depicted by the autoregulation curve (blue curve), with the lower limit, upper limit, and plateau indicated. Organ blood flow remains relatively stable via active vasodilation or vasoconstriction (indicated by the closed red circles with different sizes) when organ perfusion pressure falls within the range between the lower and upper limits (i.e. the plateau). Each individual has a baseline blood pressure, and thus, a baseline perfusion pressure for each organ. When organ perfusion pressure decreases, organ vasculature responsible for flow resistance dilates to minimise hypoperfusion/ischaemia (vasodilatory reserve); otherwise, when organ perfusion pressure increases, organ vasculature responsible for flow resistance constricts to minimise hyperperfusion (vasoconstrictive reserve). The capacity of pressure autoregulation is organ-dependent. Multiple factors can affect the position and shape of the autoregulatory curve, as indicated by the compass.[84]

图. 4. 器官灌注的压力自动调节。横轴代表器官灌注压力,纵轴代表器官血流。器官灌注压和血流之间的关系由自动调节曲线(蓝色曲线)描述,其下限、上限和平台均已注明。当器官灌注压落在下限和上限之间的范围内时(即平台),器官血流通过主动的血管扩张或血管收缩保持相对稳定(由不同大小的封闭红圈表示)。每个人都有一个基线血压,因此,每个器官也有一个基线灌注压。当器官灌注压降低时,负责血流阻力的器官血管会扩张,以尽量减少低灌注 / 缺血(血管扩张储备);否则,当器官灌注压增加时,负责血流阻力的器官血管会收缩,以尽量减少高灌注(血管收缩储备)。压力自动调节的能力是由器官决定的。多种因素可以影响自动调节曲线的位置和形状,如罗盘所示。[84]

The overarching message is that hypotension does not inevitably lead to a decrease in organ perfusion; instead, its impact on organ perfusion is dependent on the direction of the change in RVR (i.e. no change, increase, or decrease) and, when RVR decreases, on the relative decrease in RVR in comparison with the decrease in perfusion pressure. The lack of organ perfusion appraisal may be a reason for the inconsistent results among the abovementioned studies investigating the relationship between hypotension and outcomes in acute care. After all, these studies were based on outcomes that were largely determined by organ perfusion.

最重要的信息是,低血压并不必然导致器官灌注的减少;相反,它对器官灌注的影响取决于 RVR 的变化方向(即无变化、增加或减少),当 RVR 减少时,取决于 RVR 与灌注压力的减少相比的相对减少。缺乏器官灌注评估可能是上述调查急性期低血压和预后之间关系的研究中结果不一致的原因之一。毕竟,这些研究是基于主要由器官灌注决定的结果。

# 器官血流调节

Organ blood flow regulation

Organ blood flow regulation can be better explained at the level of tissue microcirculation. The regulation of tissue microcirculation takes place at the level of arterioles where capillary perfusion starts.[85] Arterioles can dilate and constrict thanks to the smooth muscle in the arteriolar wall, which leads to changes in the arteriolar radius. This is a much more robust and efficient way of flow resistance adjustment compared with changes in vascular length or blood viscosity, because resistance is inversely proportional to vascular radius to the fourth power, but only directly proportional to vascular length and blood viscosity to the first power, per Poiseuille's law. Multiple factors regulate tissue perfusion via arteriolar dilation and constriction, including (1) perfusion pressure (i.e. pressure autoregulation), (2) the autonomic nervous system, (3) circulating hormones, (4) local metabolic activity, (5) endothelial products, and (6) flow-mediated diameter changes.[85] The amalgamation of the effects exerted by these vasomotor tone modulators sets the flow resistance and regulates downstream capillary perfusion.

器官血流调节可以在组织微循环层面得到更好的解释。组织微循环的调节发生在毛细血管灌注开始的动脉血管水平。[85] 由于动脉壁上的平滑肌的作用,动脉血管可以扩张和收缩,这导致了动脉血管半径的变化。与血管长度或血液粘度的变化相比,这是一种更稳健、更有效的血流阻力调整方式,因为根据泊肃叶定律,阻力与血管半径的四次方成反比,但与血管长度和血液粘度的一次方成正比。多种因素通过动脉血管扩张和收缩调节组织灌注,包括(1)灌注压力(即压力自动调节),(2)自主神经系统,(3)循环激素,(4)局部代谢活动,(5)内皮产物,和(6)血流量介导的直径变化。这些血管运动张力调节器所发挥的作用综合起来,绝定了血流阻力并调节下游的毛细血管灌注。

The capillary bed itself can also regulate its own perfusion. Endothelial cells possess contractile fibres and are able to regulate their volume in response to external stimuli.[86] Evidence also suggests that capillaries respond to changes in BP, such that capillary diameter decreases during hypotension to the extent that red blood cell transit stops.[87]

毛细血管床本身也能调节自身的灌注。内皮细胞拥有收缩纤维,能够对外部刺激进行调节。[86] 。证据还表明,毛细血管对血压的变化有反应,如在低血压期间,毛细血管直径减少,以至于红细胞运输停止。

Pressure autoregulation, which maintains relatively stable organ perfusion despite fluctuating perfusion pressure, is just one mechanism of organ blood flow regulation (Fig. 4).[84],[88],[89] Viewing pressure autoregulation in the context of non-pressure regulatory mechanisms can be perplexing. There are two ways to consider the interplay between pressure autoregulation and non-pressure regulatory mechanisms. One way is to regard them as coexisting or parallel mechanisms, with organ perfusion as the end result of their summation. The other way is to consider non-pressure regulatory mechanisms as factors that modulate pressure autoregulation[89] ; for example hypercapnia (i.e. a metabolite) regulates pressure autoregulation by shortening the plateau and shifting it upwards.[88] Besides the interplay with non-pressure regulatory mechanisms, pressure autoregulation is also affected by physiological factors (e.g. age), chronic disease (e.g. hypertension and atherosclerosis), acute illness (e.g. traumatic brain injury), anaesthetics (e.g. sevoflurane), and drugs (e.g. calcium channel blockers).[84] Moreover, different organs have different pressure autoregulation capacities, and what are commonly considered vital organs (brain, heart, and kidney) are equipped with robust autoregulatory capacities.[84] Pressure autoregulation renders mammals, and especially their vital organs, more tolerant to acute hypotension and hypertension. During hypotension, the stable organ perfusion rendered by pressure autoregulation is consistent with the scenario described in [Figure 2]b (comparable reductions in perfusion pressure and RVR).

压力自动调节,在灌注压波动的情况下保持相对稳定的器官灌注,只是器官血流调节的一种机制(图 4)。[84], [88], [89] 在非压力调节机制的背景下看待压力自动调节可能是令人困惑的。有两种方法可以考虑压力自动调节和非压力调节机制之间的相互作用。一种方法是将它们视为共存或平行的机制,而器官灌注是它们相加的最终结果。另一种方式是将非压力调节机制视为调节压力自动调节的因素[89] ;例如,高碳酸血症(即一种代谢物)通过缩短平台期并将其上移来调节压力自动调节[88] 。除了与非压力调节机制的相互作用,压力自动调节还受到生理因素(如年龄)、慢性疾病(如高血压和动脉硬化)、急性疾病(如脑外伤)、麻醉剂(如七氟烷)和药物(如钙通道阻断剂)的影响。此外,不同的器官有不同的压力自动调节能力,而通常被认为的是重要的器官(大脑、心脏和肾脏)都有强大的自动调节能力[84] 。压力自动调节功能使哺乳动物,特别是它们的重要器官对急性低血压和高血压的耐受力更强。在低血压期间,压力自动调节所提供的稳定的器官灌注与图 2b 中描述的情况一致(灌注压力和 RVR 成比例降低)。

During sepsis and shock, macrocirculation and microcirculation are uncoupled despite the presence of normalised systemic haemodynamic variables.[90] This concept is supported by the finding that sublingual capillary microvascular flow and the percentage of perfused capillaries remain unchanged despite an increase of MAP from 65 to 85 mmHg using vasopressor infusion in septic shock patients.[91],[92] Microcirculatory dysfunction and mitochondrial depression are prominent pathophysiological features underlying the conditions of sepsis and shock and are responsible for refractory regional hypoxia and oxygen extraction deficit despite the correction of global oxygen delivery variables.[93] Whether therapies aimed at microcirculation recruitment, such as using nitric oxide donors to open the hypoperfused capillary bed or increasing the opening pressure of microcirculation, or goal-directed therapy of microcirculation guided by tissue oxygen monitoring,[94] improve outcomes remains to be determined.[95]

在脓毒症和休克期间,尽管存在正常的系统血流动力学参数,但大循环和微循环是不耦合的。[90] 。这一概念得到了以下发现的支持:尽管在脓毒症休克患者中使用血管收缩剂输注使 MAP 从 65 mmHg 上升到 85 mmHg ,但舌下毛细血管的流量和灌注毛细血管的百分比仍然没有变化。[91], [92] 微循环功能障碍和线粒体抑制是脓毒症和休克条件下的突出病理生理特征,是造成难治性局部缺氧和氧摄取不足的原因,尽管纠正了全身氧输送参数。旨在恢复微循环的疗法,如使用一氧化氮打开低灌注的毛细血管床或增加微循环的开放压力,或在组织氧监测的指导下进行微循环的目标导向治疗,[94] 是否能改善预后仍有待确定。

# 心输出量对器官灌注的重要性

Importance of cardiac output to organ perfusion

The preceding discussion highlighted that CO is not only a determinant of BP but also associates with organ perfusion. Although BP decreases in every scenario, organ perfusion likely remains stable when CO remains stable (Fig. 2b), organ perfusion likely increases when CO increases (Fig. 2c), and organ perfusion likely decreases when CO decreases (Fig. 2d–f). This observation can be better comprehended if viewing organ perfusion as a percentage share of CO because CO is ultimately distributed to various tissues and organs and the summation of their perfusion shares equals CO.[89] This view of the relationship between CO and organ perfusion enriches the traditional view regarding organ perfusion as the perfusion pressure divided by the RVR. It also highlights the importance of monitoring and maintaining CO when the ultimate goal is to ensure organ perfusion. However, we caution that this view of the relationship between CO and organ perfusion may not be applicable in conditions such as sepsis and shock, where microcirculatory dysfunction and the macrocirculation–microcirculation uncoupling are prominent features.

前面的讨论强调了 CO 不仅是 BP 的决定因素,而且还与器官灌注有关。尽管在每一种情况下血压都会下降,但当 CO 保持稳定时,器官灌注可能保持稳定(图 2b),当 CO 增加时,器官灌注可能增加(图 2c),而当 CO 减少时,器官灌注可能减少(图 2d-f)。如果把器官灌注看作是 CO 的百分比份额,就可以更好地理解这一观察结果,因为 CO 最终被分配到各个组织和器官,它们的灌注份额之和等于 CO 。这种对 CO 和器官灌注关系的看法,丰富了关于器官灌注为灌注压力除以 RVR 的传统观点。它还强调了在最终目标是确保器官灌注时监测和维持 CO 的重要性。然而,我们要提醒的是,这种关于 CO 和器官灌注之间关系的观点可能不适用于脓毒症和休克等情况,在这些情况下,微循环功能障碍和大循环与微循环脱钩是突出特点。

There is evidence suggesting the importance of maintaining CO in noncardiac surgical patients. In older adults (mean age 72 yr) with comorbid conditions undergoing elective total hip surgery with epidural anaesthesia, maintaining intraoperative MAP in the range of 45–55 mmHg or 55–70 mmHg did not lead to different outcomes (cognitive, cardiac, renal, and thromboembolic complications).[73] One potential explanation for this result was the maintained CO in patients from both groups because all patients received a low-dose i.v. epinephrine infusion. Other studies showed that epinephrine infusion at rates of 1–5 μg min−1 preserves or augments CO despite significant hypotension.[96],[97] In high-risk patients aged 50 yr or older undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery, an RCT of the effects of usual care or perioperative CO-guided haemodynamic management on a composite of predefined 30 day moderate or major complications and mortality[98] showed that CO-guided management through targeting a maximal SV via i.v. colloid infusion with a fixed low-dose dopexamine infusion (0.5 μg kg−1 min−1) led to reduction in the primary outcome (36.6%) compared with usual care (43.4%), although this difference did not reach a statistical significance (P=0.07).[98]

有证据表明,在非心脏手术患者中保持 CO 的重要性。在有合并症的老年人(平均年龄 72 岁)接受硬膜外麻醉的选择性全髋关节手术时,将术中 MAP 维持在 45-55 mmHg 或 55-70 mmHg 的范围内并没有导致不同的结果(认知、心脏、肾脏和血栓栓塞并发症)。对这一结果的一个潜在解释是两组患者都保持了 CO,因为所有患者都接受了低剂量的静脉注射肾上腺素。其他研究显示,尽管有明显的低血压,但以 1-5 微克 / 分钟的速度输注肾上腺素仍能保持或提高 CO 。在 50 岁或以上接受重大胃肠手术的高危患者中,一项关于常规救治或围术期 CO 指导下的血流动力学管理对预定的 30 天中等或主要并发症以及死亡率的影响的 RCT[98] 显示,通过静脉输注胶体同时给予固定的小剂量多巴胺输注(0.5μg kg-1 min-1)达到 SV 最大的目标,来实施 CO 指导治疗,导致首要预后(36.6%)相比传统治疗 (43.4%) 是下降的,尽管这种差异没有达到统计学意义(P=0.07)。

The importance of CO in organ perfusion was corroborated by an RCT performed in cardiac surgical patients,[72] which showed that, targeting a higher MAP (70–80 mmHg), compared with targeting a lower MAP (40–50 mmHg), during cardiopulmonary bypass did not lead to significantly different volumes or numbers of new cerebral infarcts.[72] A 40–50 mmHg MAP is equivalent to a 30–40 mmHg cerebral perfusion pressure assuming an intracranial pressure of 10 mmHg (i.e. cerebral perfusion pressure equals MAP – intracranial pressure). A cerebral perfusion pressure of 30–40 mmHg is much lower than 65 mmHg, the widely quoted lower limit of cerebral autoregulation.[88] Therefore, not seeing a worse cerebral outcome associated with this dangerously low MAP is counterintuitive. Amidst this perplexity, the most plausible explanation is how the pump flow (the equivalent of CO during cardiopulmonary bypass) was managed: it was fixed at 2.4 L min−1 m−2 irrespective of the target MAP. Therefore, if the pump flow's distribution to the brain remained unchanged, the brain would not become ischaemic despite a much lower MAP.

在心脏手术患者中进行的一项 RCT 证实了 CO 在器官灌注中的重要性,[72] 该研究显示,在体外循环期间,以较高的 MAP(70-80 mmHg )为目标,与以较低的 MAP(40-50 mmHg )为目标,不会导致新的脑梗塞的体积或数量明显不同。假设颅内压为 10mmHg,40-50mmHg 的 MAP 相当于 30-40mmHg 的脑灌注压(即脑灌注压等于 MAP - 颅内压)。30-40 mmHg 的脑灌注压远低于 65 mmHg ,这是广泛采用的脑自动调节的下限。[88] 。因此,没有看到与这种危险的低 MAP 相关的更糟糕的脑部预后是违反常理的。在这种困惑中,最合理的解释是如何管理泵流量(相当于体外循环期间的 CO):无论目标 MAP 如何,它都被固定在 2.4 L min-1 m-2。因此,如果泵的流量在大脑中的分布保持不变,尽管 MAP 低得多,大脑也不会出现缺血。

In contrast, an RCT performed in patients undergoing moderate-risk abdominal surgery showed that cardiac index and pulse pressure variation-guided haemodynamic therapy, on top of MAP-guided therapy, did not lead to improved composite outcomes compared with MAP-guided therapy only.[99] There are several explanations for this finding. First, the intervention protocols (i.e. exposures) were not distinctively different between the groups. The end result of cardiac index and pulse pressure variation-guided care was the maintenance of the targeted BP via informed intravascular volume management; however, the same BP was also targeted and accomplished in the control group. Second, the composite outcome included complications with different severities and different relevance to haemodynamics, which may decrease the power of detecting a between-group difference.[100] Third, the patients were undergoing moderate-risk abdominal surgery, and thus may have benefited from advanced haemodynamic therapy differently compared with patients undergoing high-risk surgeries.[101] However a recent sub-analysis of the Crystalloid–Colloid Study found that the worse outcomes associated with hypotension were independent of cardiac index in noncardiac surgery patients.[102]

相反,在接受中度风险腹部手术的患者中进行的一项 RCT 显示,在 MAP 指导的基础上,心脏指数和脉搏压力变化指导的血流动力学治疗,与仅有 MAP 指导的治疗相比,并没有导致综合预后的改善。[99] 对这一发现有几种解释。首先,干预方案(即,暴露)在各组之间没有明显的不同。心脏指数和脉压变异指导下的治疗的最终结果是通过依据参数的血管内容量管理维持了目标血压;然而,在对照组中,也制定并完成了同样的血压目标。第二,综合预后包括不同严重程度的并发症和各种与血流动力学相关的后果,这可能会降低检测组间差异的能力[100] 。第三,患者接受的是中度风险的腹部手术,因此与接受高风险手术的患者相比,他们可能从高级血流动力学治疗中受益不同。然而,最近对 Crystalloid-Colloid 研究的一个亚组分析发现,在非心脏手术患者中,与低血压相关的较差预后与心脏指数无关。

# 低血压的定义和分类的提议

Proposed definition and classification of hypotension

In light of the preceding discussion, hypotension is a systemic haemodynamic abnormality, defined as a measured blood pressure that is lower than a prespecified threshold, that is directly caused by changes in CO, SVR, or both, and that may or may not lead to organ and tissue hypoperfusion. There are different working definitions of hypotension; we advocate a definition that is easy to apply and relevant to patient outcomes. Thus different hypotension criteria should be established for different patient populations.[4],[8]

根据前面的讨论,低血压是一种全身血流动力学异常,定义为测量的血压低于预先指定的阈值,是由 CO、SVR 或两者的变化直接引起的,可能导致也可能不导致器官和组织灌注不足。对低血压有不同的工作定义;我们主张采用易于应用且与患者预后相关的定义。因此,应针对不同的患者群体制定不同的低血压标准。[4], [8]

In light of the different effects of hypotension on organ perfusion, we propose further classification of hypotension as (1) concerning: hypotension that leads to decreased organ perfusion; (2) possibly concerning: does not lead to decreased organ perfusion; and (3) questionable: the impact on organ perfusion cannot be confidently determined. Although a number conventionally defines hypotension, the perfusion/demand match defines whether or not hypotension is concerning.

鉴于低血压对器官灌注的不同影响,我们建议将低血压进一步分类为:(1)涉及:导致器官灌注减少的低血压;(2)可能涉及:不导致器官灌注减少;(3)有疑问:不能确定对器官灌注的影响。虽然传统的数字定义了低血压,但灌注 / 需求的匹配定义了低血压是否足以令人担忧。

# 器官灌注评估

Organ perfusion assessment

Reliable assessment of organ perfusion facilitates hypotension management in acute care. However, organ perfusion assessment is challenging in clinical practice as no monitor exists that can directly quantify the blood flow to a specific organ. Instead, indirect methods are currently used for organ perfusion assessment ([Supplementary Table S1]). Signs and symptoms occur because of organ ischaemia, such as chest pain during myocardial ischaemia and dizziness during cerebral ischaemia; these are commonly used clinically for organ perfusion assessment. Monitoring and laboratory studies are available for diagnosing organ ischaemia with varying sensitivities and specificities, such as changes in electrocardiography and troponin elevation for myocardial ischaemia. An emerging technology is tissue oximetry based on near-infrared spectroscopy, which assesses the balance between tissue oxygen consumption and supply in the tissue bed illuminated by near-infrared lights.[65],[103] This monitor is noninvasive, continuous, portable, and can be applied to different organs.[65],[104],[105] However, tissue oxygenation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy reflects tissue perfusion only when tissue metabolic rate of oxygen remains relatively stable.[106] Other technologies, such as sidestream darkfield imaging[91] and orthogonal polarisation spectral imaging,[107] have also been used for microcirculation assessment.

对器官灌注的可靠评估有助于急诊中的低血压管理。然而,器官灌注评估在临床实践中是具有挑战性的,因为没有监测仪可以直接量化特定器官的血流量。相反,目前使用间接方法进行器官灌注评估([补充表 S1])。由于器官缺血而出现体征和症状,如心肌缺血时出现胸痛,脑缺血时出现头晕;这些都是临床上常用的器官灌注评估方法。监测和实验室研究可用于诊断器官缺血,具有不同的敏感性和特异性,如心电图的变化和心肌缺血的肌钙蛋白升高。一种新兴的技术是基于近红外光谱的组织血氧仪,它可以评估近红外光照射下的组织床的组织氧消耗和供给之间的平衡。[65], [103] 这种监测是无创的、连续的、便携式的,可以应用于不同的器官。[65], [104], [105] 然而,用近红外光谱仪测量的组织血氧饱和度只有在组织氧代谢率保持相对稳定时才能反映组织灌注。[106] 其他技术,如侧流暗场成像[91] 和正交偏振光谱成像,[107] 也被用于微循环的评估。

# 涉及低血压的临床场景

Clinical scenarios involving hypotension

These examples highlight the complexity of real-world practice and underline the importance of the critical appraisal of hypotension in acute care.

这些例子突出了现实世界实践的复杂性,强调了在急性期对低血压进行严格评估的重要性。

# β 受体阻滞剂相关的低血压

Beta blocker-related hypotension

Perioperative use of beta blockers in noncardiac surgical patients is associated with increased incidence of hypotension.[25],[108],[109] Reduced CO secondary to reduced HR and SV is primarily responsible for beta blocker-related hypotension, especially when using beta blockers that do not have intrinsic sympathomimetic activity.[111] Although there may be a decrease in coronary perfusion pressure because of hypotension, beta blockers may augment coronary blood flow by increasing diastolic perfusion time via HR slowing[112] or by coronary vasodilation.[113] The level I recommendation for initiating oral beta blockers within the first 24 h in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes in the absence of heart failure, low-output state, risk of cardiogenic shock, or other contraindications highlights beta blockers' beneficial effect on the myocardial metabolic demand–supply balance.[114] Propranolol can significantly reduce cerebral perfusion pressure and cerebral blood flow, although it also reduces cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen in baboons.[115] In contrast, use of labetalol, metoprolol, oxprenolol, and sotalol did not lead to significant changes in cerebral blood flow in hypertensive patients.[116] Perioperative use of beta blockers initiated 1 day or less before noncardiac surgery reduces non-fatal myocardial infarction but increases the risk of stroke and death.[25],[109] The role of hypotension in this outcome remains unclear.

[25], [108], [109] 非心脏手术患者围手术期使用 β 受体阻滞剂与低血压发生率增加有关。继发于 HR 和 SV 降低的 CO 降低是造成 β 受体阻滞剂相关低血压的主要原因,尤其是在使用不具有内在拟交感神经活性的 β 受体阻滞剂时,[111] 。虽然低血压可能导致冠状动脉灌注压下降,但 β 受体阻滞剂可能通过减慢心率增加舒张期灌注时间[112] 或通过冠状动脉血管扩张来增加冠状动脉血流量。建议非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征患者在没有心力衰竭、低心排状态、心源性休克风险或其他禁忌症的情况下,在头 24 小时内开始口服 β 受体阻滞剂,这突出了 β 受体阻滞剂对心肌代谢供需平衡的有益作用。普萘洛尔可以明显降低脑灌注压和脑血流,尽管它也会降低狒狒的脑氧代谢率。[115] 相反,使用拉贝洛尔、美托洛尔、奥普洛尔和索他洛尔并没有导致高血压患者脑血流的明显变化。[116] 在非心脏手术前 1 天或更短时间内开始围手术期使用 β 受体阻滞剂可减少非致命性心肌梗死,但会增加卒中和死亡的风险。[25], [109] 低血压在这种结果中的作用仍不清楚。

# 尼卡地平相关的低血压

Nicardipine-related hypotension

Nicardipine is widely used as an antihypertensive drug in acute care because of its efficiency, predictability, and titratability.[82] Although it is a powerful arteriodilator and afterload/SVR/RVR modulator, nicardipine does not typically decrease preload or adversely affect myocardial contractility.[82],[117], [118], [119], [120] It increases CO because of an increase in HR and SV.[82],[117], [118], [119], [120] Nicardipine augments organ perfusion, as evidenced by increased coronary,[119],[120] cerebral,[121] renal,[122] vertebral,[122] and skeletal muscle blood flow.[82] In the face of decreased BP, the increased organ perfusion suggests that the degree of RVR decrease exceeds the degree of BP decrease (Fig. 2c). Whether nicardipine's haemodynamic profile leads to improved outcomes remains to be determined.

尼卡地平因其高效性、可预测性和可滴定性而被广泛用作急救的降压药物[82] 。尽管它是一种强大的动脉扩张剂和后负荷 / SVR/RVR 调节剂,但尼卡地平通常不会降低前负荷或对心肌收缩力产生不利影响。[82], [117], [118], [119], [120] [82], [117], [118], [119], [120] 由于 HR 和 SV 增加,它可以增加 CO。尼卡地平可增强器官的灌注,表现为冠状动脉、[119] 、[120] 脑、[121] 肾、[122] 脊椎、[122] 和骨骼肌的血流量增加。在血压下降的情况下,器官灌注的增加表明 RVR 的下降程度超过了血压的下降程度(图 2c)。尼卡地平的血流动力学特性是否会导致预后的改善,还有待确定。

# 与血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂或血管紧张素 II 受体阻断剂有关的低血压

Hypotension related to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers

Observational studies suggest that continuing angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) on the day of surgery poses an increased risk of intraoperative hypotension.[123] Although some studies show a relatively stable CO,[124],[125] a meta-analysis noted a CO increase after ACEIs/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) administration,[126] and there is evidence supporting both withholding[127] and continuation[128],[129] of ACEIs/ARBs before surgery. A meta-analysis based on five RCTs and four cohort studies failed to demonstrate an association between perioperative use of ACEIs/ARBs and mortality or major cardiac events.[123] The 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend continuing these treatments throughout the perioperative period.[130] Although continuation of ACEIs/ARBs perioperatively is associated with increased risk of hypotension, the overall evidence at present does not link this to unfavourable outcomes.

观察性研究表明,在手术当天继续使用血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(ACEI)会增加术中低血压的风险。[123] 尽管一些研究显示 CO 相对稳定,[124],[125] 一项荟萃分析指出在使用 ACEI / 血管紧张素 II 受体阻断剂(ARBs)后 CO 会增加,[126] 并且有证据支持术前暂停使用 ACEI/ARBs[127] 和继续使用[128],[129] 一项基于 5 项 RCT 和 4 项队列研究的荟萃分析未能证明围手术期使用 ACEI/ARB 与死亡率或主要心脏事件之间存在关联。2014 年美国心脏病学院 / 美国心脏协会指南建议在整个围手术期继续使用这些治疗方法[130] 。虽然围手术期继续使用 ACEI/ARB 与低血压风险增加有关,但目前的总体证据并没有将其与不良的预后联系起来。

# 神经阻滞相关的低血压

Neuraxial block-related hypotension

Hypotension is common after neuraxial block in obstetric and surgical patients. Neuraxial block-related hypotension is caused by a decrease in SVR, not CO. A study of patients undergoing elective Caesarean delivery showed that although systolic BP decreased 7% below baseline, CO increased 19% from baseline 20 min after the neuraxial block.[131] In patients undergoing hip surgery under hypotensive epidural anaesthesia (maintaining MAP ≤50 mmHg while infusing epinephrine to support circulation), an observational study showed that cerebral blood flow velocity was well maintained, despite MAPs well below the commonly accepted lower limit of cerebral autoregulation.[132] However, there was considerable inter-individual heterogeneity, with 23% of patients having >20% reduction in cerebral blood flow velocity.[133] In patients with severe coronary artery disease, an observational study showed that high thoracic epidural anaesthesia did not change coronary perfusion pressure or myocardial blood flow.[133] This study also showed that thoracic epidural block increases the diameter of stenotic, but not non-stenotic, epicardial coronary artery segments.[133] In patients with ischaemic heart disease, high thoracic epidural analgesia was able to partly normalise the myocardial blood flow response to sympathetic stimulation.[134] When low-dose epinephrine was infused during epidural anaesthesia, patients who had a lower MAP (45–55 mmHg) did not experience more complications than patients who had a higher MAP (55–70 mmHg).[73] A population-based cohort study, using data from propensity score-matched patients, concluded that epidural anaesthesia is associated with a small reduction in 30 day mortality.[135] Therefore, the available evidence suggests that as long as extreme hypotension is avoided, neuraxial block-related hypotension does not appear to be harmful.

低血压在产科和外科病人的神经轴阻滞后很常见。与神经轴阻滞相关的低血压是由 SVR 的下降引起的,而不是 CO。一项对选择性剖腹产患者的研究显示,尽管收缩压比基线下降了 7%,但在神经轴阻滞后 20 分钟,CO 比基线增加了 19%[[131] (#131)] 。在低血压硬膜外麻醉(维持 MAP≤50mmHg,同时输注肾上腺素支持循环)下进行髋关节手术的患者,一项观察性研究显示,尽管 MAP 远低于普遍接受的脑自主调节的下限,但脑血流速度仍保持良好。然而,个体间存在相当大的异质性,23% 的患者脑血流速度下降 > 20%。[133] 对于严重的冠状动脉疾病患者,一项观察性研究显示,高位胸段硬膜外麻醉并没有改变冠状动脉灌注压和心肌血流。这项研究还表明,胸腔硬膜外阻滞会增加狭窄的冠状动脉段的直径,但不会增加非狭窄的冠状动脉段的直径。[133] 在缺血性心脏病患者中,高位胸段硬膜外镇痛能够部分地使心肌对交感神经刺激的血流反应正常化。[134] 当硬膜外麻醉期间注入小剂量肾上腺素时,MAP 较低(45-55 mmHg )的患者并没有比 MAP 较高(55-70 mmHg )的患者出现更多的并发症。[73] 一项基于人群的队列研究,使用倾向性评分匹配的病人的数据,得出的结论是硬膜外麻醉与 30 天死亡率的小幅下降有关。[135] 因此,现有的证据表明,只要避免极度低血压,神经轴阻滞相关的低血压似乎并不有害。

# 急性贫血相关的低血压

Acute anaemia-related hypotension

Acute anaemia leads to increased CO,[136] increased cerebral blood flow,[137] and increased coronary blood flow[138] as a compensatory mechanism to boost oxygen delivery when arterial blood oxygen content is reduced.[139] Acute anaemia also decreases blood viscosity and SVR.[136] There appears to be an interplay between changes in blood viscosity and changes in CO during acute anaemia.[136] Acute anaemia can lead to hypotension depending on the relative changes between CO and SVR. There was initially a concern that co-occurrence of anaemia and hypotension during cardiopulmonary bypass could be associated with an increased risk of postoperative acute kidney injury[60] ; however, this was later refuted by a large cohort study.[61] In high-risk patients undergoing hip fracture repair, liberal transfusion (maintaining a haemoglobin>100 g L−1) and restrictive transfusion (maintaining a haemoglobin no>80 g L−1 or keeping the patient free from anaemia-related symptoms) did not lead to different outcomes.[140],[141] At present, there is no evidence attesting to adverse effects associated with acute anaemia-related hypotension.

急性贫血导致 CO 增加,[136] 脑血流量增加,[137] 和冠状动脉血流量增加[138] ,这是动脉血氧含量减少时提高氧输送的一种补偿机制[139] 。急性贫血也会降低血液粘度和 SVR。[136] 在急性贫血期间,血液粘度的变化和 CO 的变化之间似乎存在着相互作用。急性贫血可导致低血压,这取决于 CO 和 SVR 之间的相对变化。最初有人担心,在体外循环术中,贫血和低血压同时出现,可能与术后急性肾损伤的风险增加有关[60] ;但是,这一点后来被一项大型队列研究所驳斥。在接受髋部骨折修复的高危患者中,自由输血(保持血红蛋白 > 100g L-1)和限制性输血(保持血红蛋白不 > 80g L-1 或保持患者无贫血相关症状)并没有导致不同的结果。[140],[141]目前,没有证据证明与急性贫血相关的低血压有不良影响。

# 丙泊酚相关的低血压

Propofol-related hypotension

Hypotension is common after anaesthesia induction using propofol.[142] The effects of propofol on haemodynamics are mediated primarily via inhibition of sympathetic nervous activity, as opposed to direct vasomotor tone changes.[142] Propofol impairs baroreflex,[143] decreases SVR,[144] decreases venous return,[145] and can reduce CO.[144],[146] The impact of propofol on organ perfusion varies between brain and other organs. Propofol reduces cerebral perfusion but does not cause ischaemia because of the proportional reduction in cerebral metabolic activity.[147], [148], [149] There is a lack of direct evidence on its effects on perfusion of non-brain organs, although indirect evidence suggests that it may not have adverse effects.[150] Propofol may cause some degree of CO reduction[144],[146] ; however, this may not be consequential. As propofol can cause up to a 30% decrease in cerebral blood flow,[147] it is likely that the reduced cerebral perfusion may be mainly responsible for the reduced CO because the brain accounts for up to 20% of CO.[151] At present, there is no evidence attesting to an adverse effect exerted by propofol-related hypotension.

使用丙泊酚进行麻醉诱导后,低血压很常见。[142] 丙泊酚对血流动力学的影响主要是通过抑制交感神经活动来介导的,而不是直接改变血管运动张力。[143] 降低 SVR,[144] 降低静脉回流,[145] 并可降低 CO。丙泊酚对器官灌注的影响在大脑和其他器官之间有所不同。[147], [148], [149] 丙泊酚会减少脑灌注,但不会导致缺血,因为脑代谢活动会按比例减少。目前缺乏关于其对非脑器官灌注影响的直接证据,但间接证据表明其可能没有不良影响。[150] 丙泊酚可能会导致某种程度的 CO 减少[144], [146] ;但是,这可能不会有什么影响。由于丙泊酚可导致脑血流减少多达 30%,[147] 因此,脑灌注量的减少可能是造成 CO 减少的主要原因,因为脑部占 CO 的比例高达 20%[151] 。目前,没有证据证明丙泊酚相关的低血压产生了不良影响。

# 脓毒症休克相关的低血压

Septic shock-related hypotension

Septic shock is characterised by distributive organ hypoperfusion in the face of hypotension, vasodilation, and, frequently, increased CO.[152], [153], [154], [155], [156] Several studies have found that when MAP is increased from 65 to 85 mmHg using norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock, CO increases by 8–20%.[91],[157], [158], [159] However, the increase in CO does not consistently translate into an increase in organ perfusion. Some studies show that norepinephrine infusion, which increased MAP from 65 to 85 mmHg, did not improve tissue perfusion.[91],[157],[158] In contrast, other studies show that norepinephrine infusion leads to improved tissue perfusion.[159],[160] Among the multiple potential reasons for this discrepancy, flow redistribution may be responsible for the inconsistent changes in tissue perfusion.[161],[162] Even though an organ may appear to have sufficient gross perfusion, it can still undergo regional tissue ischaemia and hypoxia because of microcirculatory and mitochondrial dysfunction[93] or unmet hypermetabolic activity.[163] The challenges of treating haemodynamic abnormalities in septic shock were highlighted by a multicentre RCT,[74] which showed that targeting MAP of 80–85 mmHg, as compared with 65–70 mmHg, did not lead to differences in mortality at either 28 or 90 days.[74] Based on this, septic shock is neither caused by hypotension nor can it be cured by BP-increasing treatment.

脓毒症休克的特点是在低血压、血管扩张的情况下出现分布性器官灌注不足,而且经常出现 CO 值增加。[152], [153], [154], [155], [156] 一些研究发现,在脓毒症休克患者中使用去甲肾上腺素输液将 MAP 从 65mmHg 提高到 85mmHg 时,CO 增加 8-20%。[91], [157], [158], [159] 然而, CO 的增加并不总是转化为器官灌注的增加。一些研究显示,输注去甲肾上腺素,使 MAP 从 65 mmHg 增加到 85 mmHg ,并没有改善组织灌注。[91], [157], [158] 相反,其他研究却显示,输注去甲肾上腺素会导致组织灌注的改善。[159], [160] 在造成这种差异的多种潜在原因中,血流重新分布可能是造成组织灌注变化不一致的原因。[161], [162] 即使一个器官看起来有足够的总灌注量,但由于微循环和线粒体功能障碍[93] 或高代谢活动得不到满足,它仍可能发生区域性组织缺血和低氧。一项多中心 RCT 强调了治疗脓毒症休克中血流动力学异常的挑战,[74] 该研究显示,将 MAP 定为 80-85 mmHg ,与 65-70 mmHg 相比,在 28 天或 90 天内的死亡率并无差异[74] 。基于此,脓毒症休克既不是由低血压引起的,也不能通过提高血压的治疗来治愈。

# 临床意义

Clinical implications

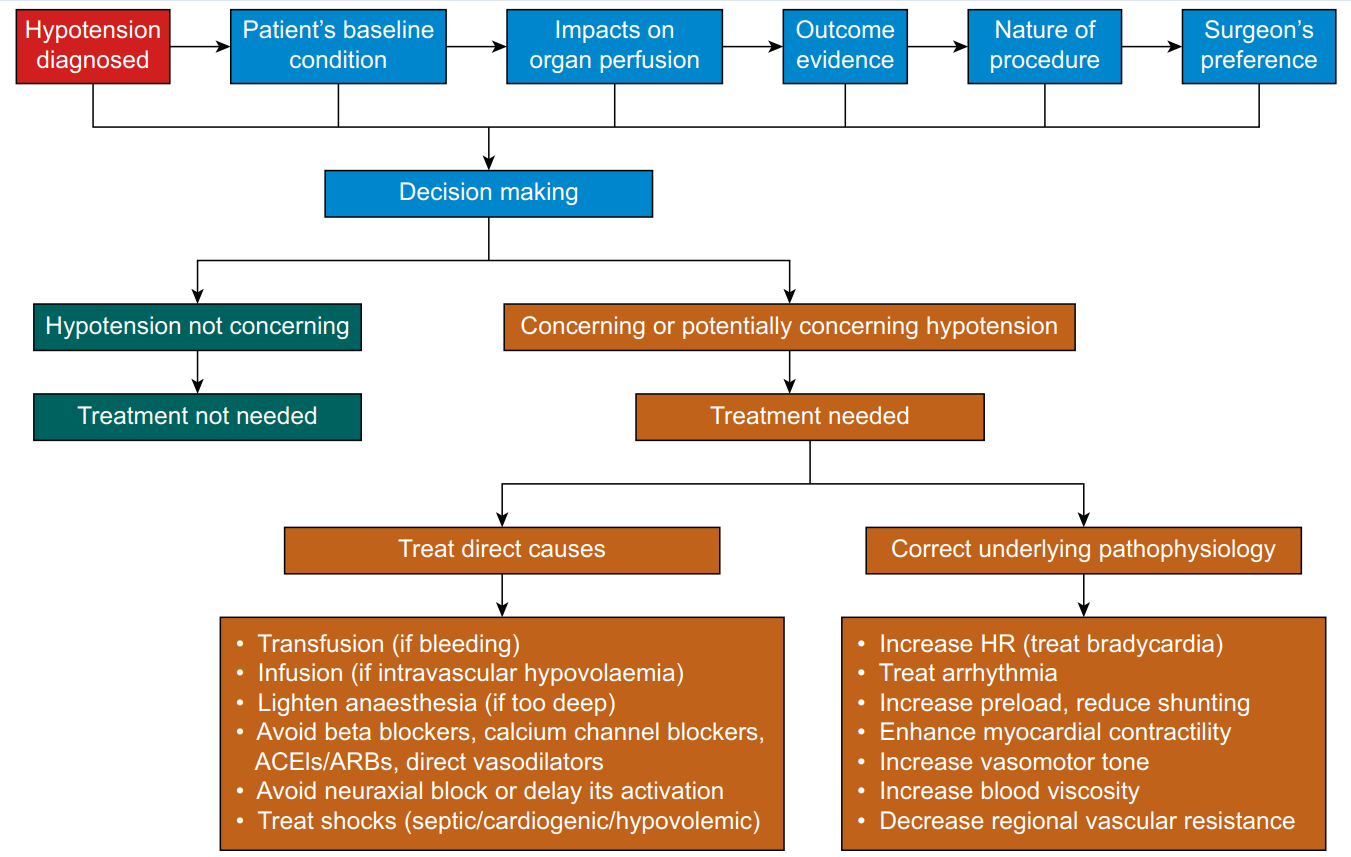

BP is the most common haemodynamic variable monitored in patient care (as a vital sign). Although HR is also monitored (as a vital sign), there is a consensus that it does not provide the same haemodynamic information as BP. The key message of the above discussion is the ‘heterogeneity’ of hypotension effects on underlying pathophysiology and its impact on organ perfusion and outcomes. The clinical management of hypotension follows the axis of diagnosis–decision-making–intervention (Fig. 5); it is critical to remember that the goal is to ensure organ perfusion, not to correct a number.

血压是病人治疗中最常见的血流动力学参数监测(作为生命体征)。尽管心率也被监测(作为一个生命体征),但人们一致认为它不能提供与血压相同的血流动力学信息。上述讨论的关键信息是低血压对基础病理生理学的影响的 "异质性" 及其对器官灌注和预后的影响。低血压的临床管理遵循诊断 - 决策 - 干预的轴线(图 5);关键是要记住,目标是确保器官灌注,而不是纠正一个数字。

Fig. 5. The axis of diagnosis–decision-making–intervention for hypotension management. The first step is to diagnose hypotension based on both clinical experience and the available consensus.[8] The second step is to decide to treat or not to treat hypotension, which is a complicated decision-making process that needs to take the patient's baseline condition, effects on organ perfusion, outcome evidence, and nature of the procedure. The third step is intervention if the decision is to treat hypotension. The intervention follows two approaches: one is to treat direct causes, and the other is to correct the underlying pathophysiology responsible for hypotension. These two lines of treatment approaches may sometimes overlap.

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker.

图. 5. 低血压管理的诊断 - 决策 - 干预轴。第一步是根据临床经验和现有共识对低血压进行诊断[8] 。第二步是决定治疗或不治疗低血压,这是一个复杂的决策过程,需要考虑病人的基线状况、对器官灌注的影响、预后的证据和手术的性质 [以及外科医生的选择]。第三步是干预,如果决定治疗低血压。干预遵循两种方法:一种是治疗直接原因,另一种是纠正导致低血压的潜在病理生理学。这两条线的治疗方法有时可能重叠。

ACEI,血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂;ARB,血管紧张素 II 受体阻断剂。

The first step in managing hypotension is to determine whether the BP decreases below a prespecified threshold. This can be challenging, as in perioperative care, the thresholds used to define hypotension are primarily experience-based owing to the lack of convincing RCT-based evidence.[4],[8] In critical care, the criteria for hypotension are also controversial and appear to depend on the patient population. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommends an initial target MAP of 65 mmHg in patients with septic shock requiring vasopressors based on moderate-quality evidence.[156] In contrast, patients with acute ischaemic stroke mandate a much higher BP for brain perfusion, although the minimal BP that is acceptable remains to be determined.[164],[165]

处理低血压的第一步是确定血压是否下降到预先指定的阈值以下。这可能具有挑战性,因为在围手术期治疗中,由于缺乏令人信服的 RCT 证据,用于定义低血压的阈值主要是基于经验。[4], [8] 在重症监护中,低血压的标准也是有争议的,似乎取决于病人的情况。拯救脓毒症运动根据中等质量的证据,建议需要使用升压药的脓毒症休克患者的初始目标 MAP 为 65mmHg[156] 。相比之下,急性缺血性卒中患者需要更高的血压来保证脑灌注,但可以接受的最低血压仍有待确定。[164],[165]

The second step in managing hypotension is decision-making, that is deciding whether the diagnosed hypotension requires treatment. The decision-making process must take the patient's baseline condition, the impact on organ perfusion, outcomes evidence, the nature of the procedure, and the surgeon's preference into consideration. This is a complicated process, and there is no single criterion that fits all scenarios. Haemodynamics need to be meticulously managed in patients at risk of organ ischaemia because of either arterial stenotic disease (e.g. coronary artery disease) or the procedure itself (e.g. carotid artery clamping for endarterectomy). If the surgeon insists on lowering BP during signs of organ ischaemia, the situation should be discussed with the surgeon, and an observation should be made regarding whether improving CO or decreasing organ metabolic demand can reverse organ ischaemia. The outcome evidence upon which the decision-making process is based needs to be consistent and free from significant bias and limitations. At present, existing evidence does not consistently support the notion that a higher BP target leads to improved outcomes. Individualised BP management is promising,[67] but challenges include what the baseline BP is and how to determine it.

低血压管理的第二步是决策,即决定诊断出的低血压是否需要治疗。决策过程必须考虑到病人的基线状况、对器官灌注的影响、预后证据、手术的性质和外科医生的偏好。这是一个复杂的过程,没有适合所有情况的单一标准。对于因动脉狭窄疾病(如冠状动脉疾病)或手术本身(如颈动脉夹闭术)而有器官缺血风险的病人,血流动力学需要得到细致的管理。如果外科医生在出现器官缺血的迹象时坚持降低血压,应与外科医生讨论这种情况,并观察改善 CO 或减少器官代谢需求是否能逆转器官缺血。决策过程所依据的预后证据需要是一致的,没有明显的偏倚和局限性。目前,在较高的血压目标会导致改善预后的观点上,现有的支持证据并不一致。个体化血压管理是有前景的,[67] 但面临的挑战包括什么是基线血压以及如何确定它。

It should be noted that different organs have different perfusion regulation and different tolerance of ischaemia.[84] For example the brain cannot tolerate even a few minutes of ischaemia,[166] whereas muscle can tolerate up to 2 h of ischaemia, as exemplified by the prevalent use of a tourniquet during limb procedures.[167] Therefore, the impact of hypotension on organ perfusion is also organ-dependent, and organs that have poor tolerance of ischaemia should be closely monitored and prioritised in haemodynamic management.[84]

应该注意的是,不同的器官有不同的灌注调节,对缺血的耐受性也不同。[84] 例如,大脑甚至不能容忍几分钟的缺血,[166] 而肌肉可以容忍长达 2 小时的缺血,在肢体手术中普遍使用止血带就是一个例子[167] 。因此,低血压对器官灌注的影响也与器官有关,对缺血耐受性差的器官应密切监测,并在血流动力学管理中优先考虑。[[84] (#84)] 。

The third step is intervention if the decision is to correct the hypotension. There are two different lines of approach for treatment of hypotension. One addresses the cause of the hypotension, including – but not limited to – transfusion if there is active bleeding, infusion if there is intravascular volume depletion, lightening anaesthesia if it is too deep, avoiding beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACEIs/ARBs, and direct vasodilators, avoiding neuraxial blocks or delaying their activation, and treating septic, cardiogenic, or hypovolaemic shock. The other line is dealing with the haemodynamic changes that lead to hypotension by referring to the haemodynamic pyramid (Fig. 1) and the pressure–output–resistance triangle (Fig. 2). This approach includes the following treatments, depending on patient status: treat bradycardia, treat arrhythmia, increase preload, enhance myocardial contractility, increase vasomotor tone, and increase blood viscosity. The status of intravascular volume and preload can be assessed using dynamic indices, such as pulse pressure variation and stroke volume variation. However, performance of these dynamic indices may vary during hypotension or normotension, which deserves further investigation.

如果决定纠正低血压,第三步是干预。对低血压的治疗有两种不同的方法。一种是针对低血压的原因,包括 -- 但不限于 -- 如果有活动性出血则输血,如果有血管内容量不足则输液,如果麻醉过深则减轻麻醉,避免使用 β 受体阻滞剂、钙通道阻滞剂、ACEI/ARBs 和直接血管扩张剂,避免神经轴阻滞或避免延长其作用,以及治疗脓毒性、心源性或低血容量休克。另一种是参照血流动力学金字塔(图 1)和血压 - 心输出量 - 血管阻力三角形(图 2)来处理导致低血压的血流动力学变化。这种方法包括以下治疗,取决于病人的状态:治疗心动过缓,治疗心律失常,增加前负荷,增强心肌收缩力,增加血管运动张力,增加血液粘度。血管内容量和前负荷的状态可以用动态指标来评估,如脉压变异和每搏量变异。然而,这些动态指标的表现在低血压或正常血压时可能有所不同,这值得进一步研究。

# 结论

Hypotension has heterogenous underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and effects on organ perfusion and patient outcomes in acute care. Hypotension does not always lead to organ hypoperfusion; in fact, it may not affect or may even increase organ perfusion, depending on the relative changes between the perfusion pressure and the RVR and pressure autoregulation. Available outcome evidence should be interpreted recognising their various biases and limitations. Overall RCT evidence does not support the notion that a higher BP target always leads to improved outcomes. Management of hypotension follows the diagnosis–decision-making–intervention axis, and it is challenging to define hypotension using one threshold for different patient populations under different clinical situations. When dealing with hypotension, it is essential to consider how well the BP is driving organ perfusion rather than focusing on a fixed BP value. To treat or not to treat hypotension is a complicated decision-making process that needs to take into account the patient's baseline condition, effects on organ perfusion, outcome evidence, and the nature of the procedure. Treatment follows two approaches: treating the direct causes or correcting the underlying haemodynamic changes responsible for the hypotension. These two approaches may sometimes overlap. Hence, the focus is on the heterogeneity of hypotension's underlying pathophysiology, effects on organ perfusion and patient outcomes.

低血压有不同的潜在病理生理机制,对器官灌注和急性期病人的影响也不同。低血压并不总是导致器官灌注不足;事实上,它可能不影响甚至可能增加器官灌注,这取决于灌注压力和 RVR 以及压力自动调节之间的相对变化。在解释现有的预后证据时,应认识到它们的各种偏倚和局限性。总体而言,RCT 证据并不支持较高的血压目标总是导致改善预后的观点。低血压的管理遵循诊断 - 决策 - 干预的轴线,在不同的临床情况下对不同的患者群体使用一个阈值来定义低血压是很有挑战性的。在处理低血压时,必须考虑血压对器官灌注的推动作用,而不是专注于一个固定的血压值。治疗或不治疗低血压是一个复杂的决策过程,需要考虑到病人的基线状况、对器官灌注的影响、预后证据和手术的性质。治疗遵循两种方法:治疗直接原因或纠正导致低血压的潜在血流动力学变化。这两种方法有时可能会重叠在一起。因此,重点是低血压的基本病理生理学的异质性,对器官灌注的影响和病人的预后。

# 参考文献

1. Williams B., Mancia G., Spiering W., et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104.

动脉高血压管理指南。

2. Whelton P.K., Carey R.M., Aronow W.S., et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248.

成人高血压的预防、检测、评估和管理指南:美国心脏病学院 / 美国心脏协会临床实践指南工作组的报告。

3. Foëx P., Sear J.W. Implications for perioperative practice of changes in guidelines on the management of hypertension: challenges and opportunities. Br J Anaesth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.006. Advance Access published on June 11.

高血压管理指南的变化对围手术期实践的影响:挑战和机遇。

4. Sessler D., Bloomstone J.A., Aronson S., et al. Perioperative Quality Initiative consensus statement on intraoperative blood pressure, risk and outcomes for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:563–574.

围手术期质量倡议关于选择性手术术中血压、风险和预后的共识声明。

5. Bijker J.B., van Klei W.A., Kappen T.H., van Wolfswinkel L., Moons K.G., Kalkman C.J. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:213–220.

术中低血压的发生率与所选定义有关:文献定义应用于使用自动数据收集的回顾性队列。

6. Brady K.M., Hudson A., Hood R., DeCaria B., Lewis C., Hogue C.W. Personalizing the definition of hypotension to protect the brain. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:170–179.

个人化的低血压定义以保护大脑。

7. Vernooij L.M., van Klei W.A., Machina M., Pasma W., Beattie W.S., Peelen L.M. Different methods of modelling intraoperative hypotension and their association with postoperative complications in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1080–1089.

不同的术中低血压建模方法及其与接受非心脏手术患者术后并发症的关系。

8. Meng L., Yu W., Wang T., Zhang L., Heerdt P.M., Gelb A.W. Blood pressure targets in perioperative care. Hypertension. 2018;72:806–817.

围手术期治疗中的血压目标。

9. Maheshwari K., Nathanson B.H., Munson S.H., et al. The relationship between ICU hypotension and in-hospital mortality and morbidity in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:857–867.

脓毒症患者在 ICU 的低血压与院内死亡率和发病率之间的关系。

10. Mascha E.J., Yang D., Weiss S., Sessler D.I. Intraoperative mean arterial pressure variability and 30-day mortality in patients having noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:79–91.

术中平均动脉压变化与非心脏手术患者的 30 天死亡率。

11. Abbott T.E.F., Pearse R.M., Archbold R.A., et al. A Prospective international multicentre cohort study of intraoperative heart rate and systolic blood pressure and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: results of the VISION study. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1936–1945.

术中心率和收缩压与非心脏手术后心肌损伤的前瞻性国际多中心队列研究:VISION 研究的结果。

12. Monk T.G., Bronsert M.R., Henderson W.G., et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and hypertension and 30-day postoperative mortality in noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:307–319.

术中低血压和高血压与非心脏手术术后 30 天死亡率的关系。

13. Monk T.G., Saini V., Weldon B.C., Sigl J.C. Anesthetic management and one-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:4–10.

麻醉管理与非心脏手术后一年的死亡率。

14. Sessler D.I., Sigl J.C., Kelley S.D., et al. Hospital stay and mortality are increased in patients having a "triple low" of low blood pressure, low bispectral index, and low minimum alveolar concentration of volatile anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1195–1203.

低血压、低双峰指数和低挥发性麻醉最低肺泡浓度的 "三低" 患者的住院时间和死亡率都增加。

15. Sprung J., Abdelmalak B., Gottlieb A., et al. Analysis of risk factors for myocardial infarction and cardiac mortality after major vascular surgery. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:129–140.

大血管手术后心肌梗死和心脏死亡的危险因素分析。

16. Willingham M.D., Karren E., Shanks A.M., et al. Concurrence of intraoperative hypotension, low minimum alveolar concentration, and low bispectral index is associated with postoperative death. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:775–785.

术中低血压、低最低肺泡浓度和低双谱指数与术后死亡有关。

17. Pietropaoli J.A., Rogers F.B., Shackford S.R., Wald S.L., Schmoker J.D., Zhuang J. The deleterious effects of intraoperative hypotension on outcome in patients with severe head injuries. J Trauma. 1992;33:403–407.

术中低血压对严重颅脑损伤患者结局的有害影响。

18. Reich D.L., Wood R.K., Jr., Emre S., et al. Association of intraoperative hypotension and pulmonary hypertension with adverse outcomes after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:699–702.

术中低血压和肺动脉高压与正位肝移植后不良后果的关系。

19. Sessler D.I., Meyhoff C.S., Zimmerman N.M., et al. Period-dependent associations between hypotension during and for four days after noncardiac surgery and a composite of myocardial infarction and death: a substudy of the POISE-2 trial. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:317–327.

非心脏手术期间和术后四天的低血压与心肌梗死和死亡的关系:POISE-2 试验的子研究。

20. Goldman L., Caldera D.L., Southwick F.S., et al. Cardiac risk factors and complications in non-cardiac surgery. Medicine. 1978;57:357–370.

非心脏手术的心脏危险因素和并发症。

21. Ziser A., Plevak D.J., Wiesner R.H., Rakela J., Offord K.P., Brown D.L. Morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients undergoing anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:42–53.

肝硬化患者接受麻醉和手术的发病率和死亡率。

22. Willingham M., Ben Abdallah A., Gradwohl S., et al. Association between intraoperative electroencephalographic suppression and postoperative mortality. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:1001–1008.

术中脑电图抑制与术后死亡率的关系。

23. White S.M., Moppett I.K., Griffiths R., et al. Secondary analysis of outcomes after 11,085 hip fracture operations from the prospective UK Anaesthesia Sprint Audit of Practice (ASAP-2) Anaesthesia. 2016;71:506–514. [[Google Scholar]&author=S.M.+White&author=I.K.+Moppett&author=R.+Griffiths&volume=71&publication_year=2016&pages=506-514&pmid=26940645&)].

来自前瞻性英国麻醉 Sprint 实践稽查 (ASAP-2) 的 11085 例髋部骨折手术后结局的次要分析。

24. Cheng X.Q., Wu H., Zuo Y.M., et al. Perioperative risk factors and cumulative duration of "triple-low" state associated with worse 30-day mortality of cardiac valvular surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2017;31:387–395.

围手术期风险因素和 “三低” 状态的累积持续时间与心脏瓣膜手术 30 天死亡率较差相关。

25. Devereaux P.J., Yang H., Yusuf S., et al. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1839–1847. [[Google Scholar]:+a+randomised+controlled+trial&author=P.J.+Devereaux&author=H.+Yang&author=S.+Yusuf&volume=371&publication_year=2008&pages=1839-1847&pmid=18479744&)].

琥珀酸美托洛尔缓释剂对非心脏手术患者的影响(POISE 试验):一项随机对照试验。

26. Brunaud L., Nguyen-Thi P.L., Mirallie E., et al. Predictive factors for postoperative morbidity after laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis in 225 patients. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1051–1059.

腹腔镜肾上腺切除术治疗嗜铬细胞瘤后发病率的预测因素:225 例患者的多中心回顾性分析。

27. Salmasi V., Maheshwari K., Yang D., et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:47–65.

术中低血压(由基线降低或绝对阈值定义)与非心脏手术后急性肾脏和心肌损伤之间的关系:一项回顾性队列分析。

28. Sun L.Y., Wijeysundera D.N., Tait G.A., Beattie W.S. Association of intraoperative hypotension with acute kidney injury after elective noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:515–523.

术中低血压与选择性非心脏手术后急性肾损伤的关系。

29. Walsh M., Devereaux P.J., Garg A.X., et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–515.

术中平均动脉压与非心脏手术后临床预后之间的关系:对低血压的经验定义。

30. Charlson M.E., MacKenzie C.R., Gold J.P., Ales K.L., Topkins M., Shires G.T. Intraoperative blood pressure. What patterns identify patients at risk for postoperative complications? Ann Surg. 1990;212:567–580.

术中血压。哪些模式可以识别有术后并发症风险的病人?

31. Hallqvist L., Granath F., Huldt E., Bell M. Intraoperative hypotension is associated with acute kidney injury in noncardiac surgery: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35:273–279.

术中低血压与非心脏手术的急性肾损伤有关:一项观察性研究。

32. Tallgren M., Niemi T., Poyhia R., et al. Acute renal injury and dysfunction following elective abdominal aortic surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:550–555.

急性肾损伤和选择性腹主动脉手术后功能障碍。

33. House L.M., Marolen K.N., St Jacques P.J., McEvoy M.D., Ehrenfeld J.M. Surgical Apgar score is associated with myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:395–402.

手术 Apgar 评分与非心脏手术后心肌损伤有关。

34. Kim B.H., Lee S., Yoo B., et al. Risk factors associated with outcomes of hip fracture surgery in elderly patients. Kor J Anesthesiol. 2015;68:561–567.

与老年患者髋部骨折手术预后有关的风险因素。

35. van Waes J.A., van Klei W.A., Wijeysundera D.N., van Wolfswinkel L., Lindsay T.F., Beattie W.S. Association between intraoperative hypotension and myocardial injury after vascular surgery. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:35–44.

血管手术后术中低血压和心肌损伤之间的关系。

36. Alcock R.F., Kouzios D., Naoum C., Hillis G.S., Brieger D.B. Perioperative myocardial necrosis in patients at high cardiovascular risk undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. Heart. 2012;98:792–798.

接受选择性非心脏手术的心血管高风险患者的围手术期心肌坏死。